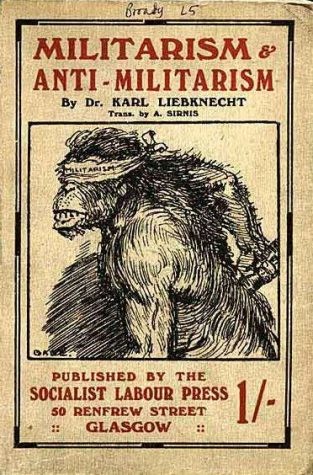

Militarism, in essence, is more than just a strong army; it’s a societal ethos that glorifies military power and influence. As Alfred Vagts, a distinguished German historian and World War I veteran, astutely observed, militarism signifies “the domination of the military man over the civilian, an undue preponderance of military demands, an emphasis on military considerations.” In the decades leading up to 1914, the major European powers were increasingly gripped by this philosophy, each to varying degrees. This pervasive militarism wasn’t the sole trigger for World War I, but it undeniably laid a crucial foundation, fostering an environment where war became not just conceivable, but almost inevitable.

Defining Militarism: More Than Just Military Might

Militarism permeated European society throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, extending its reach far beyond the barracks and battlefields. Governments across the continent found themselves increasingly swayed, and in some cases, dominated by military figures, agendas, and priorities. High-ranking generals and admirals often functioned as de facto ministers, wielding considerable influence over political leaders, shaping domestic policies, and relentlessly advocating for increased defense budgets and military expansion.

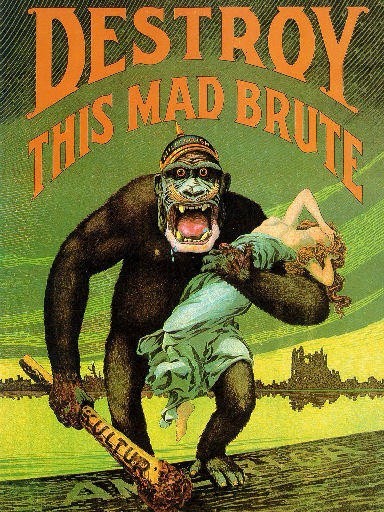

This surge in militaristic sentiment cultivated a dangerous offspring: a relentless arms race. This race spurred the development of groundbreaking military technologies and triggered exponential growth in defense spending. Militarism’s impact transcended mere policy; it deeply infiltrated culture, media, and public opinion. The press, a powerful tool in shaping public perception, lionized military leaders as national heroes, depicted rival nations as aggressors, and consistently engaged in inflammatory “war talk,” normalizing the idea of conflict.

While militarism alone cannot be solely blamed for initiating World War I – a specific catalyst and political meltdown were still required – it undeniably cultivated a climate where war was perceived as a viable, even preferable, solution for resolving international disputes and dealing with rival nations, overshadowing diplomacy and negotiation.

The Symbiotic Relationship: Militarism, Nationalism, and Imperialism

Militarism, nationalism, and imperialism were not isolated ideologies but rather deeply intertwined forces, each reinforcing the other in a dangerous dance towards war. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, military might was unequivocally equated with national and imperial prestige. A powerful nation, in this worldview, needed a formidable military to safeguard its interests and enforce its policies on the global stage. Robust armies and navies were deemed indispensable for defending the homeland, protecting burgeoning imperial possessions and trade networks across the globe, and deterring potential threats and rivals lurking on the horizon.

War, while ideally avoided, was also considered a legitimate instrument to advance a nation’s political and economic objectives. Echoing this sentiment, the renowned Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously wrote in 1832 that war was simply “a continuation of policy by other means.” This perspective, though written decades before WWI, encapsulates the prevailing attitude in pre-war Europe.

In the 19th-century European mindset, politics and military power became inextricably linked, mirroring the modern-day inseparable relationship between politics and economic management. Governments and leaders who failed to maintain military forces capable of asserting national will were often viewed as weak, inept, or lacking in resolve. This created immense pressure to constantly expand and modernize military capabilities.

“The belief in war as a test of national power and a proof of national superiority added a scientific base to the cult of patriotism… In Britain, a real effort was made to teach boys that success in war depended upon the patriotism and military spirit of the nation, and that preparation for war would strengthen ‘manly virtue’ and ‘patriotic ardour’.” Zara Steiner, historian

The Seed of Militarism: Prussian Influence

The Kingdom of Prussia, nestled in northern Germany, is widely recognized as the birthplace of European militarism. Both the German government and its formidable armed forces were meticulously modeled after the Prussian system. Significantly, many influential German politicians and generals hailed from the Junker class – the landowning Prussian nobility, further cementing the militaristic ethos at the heart of German power.

Prior to the unification of Germany in 1871, Prussia stood as the most dominant of the German states. The Prussian army underwent a significant transformation and modernization in the 1850s under the astute leadership of Field Marshal von Moltke the Elder. Under von Moltke’s command, the Prussian army revolutionized its strategies, implemented rigorous officer training programs, adopted cutting-edge weaponry, and streamlined its command and communication structures for maximum efficiency.

Prussia’s decisive military triumph over France in 1871 emphatically showcased its army as the most formidable and effective military force in Europe. This victory not only solidified German unification but also allowed Prussian militarism and burgeoning German nationalism to become deeply intertwined and mutually reinforcing. Prussian commanders, personnel, and military doctrines became the bedrock of the newly formed German imperial army. While the German Kaiser held the title of supreme commander, he heavily relied on a military council and chief of the general staff, composed primarily of Junker aristocrats and seasoned career officers, effectively placing military decision-making in the hands of a select elite. Critically, the Reichstag, Germany’s elected civilian parliament, was relegated to a mere advisory role when it came to military affairs, highlighting the imbalance of power and the dominance of the military establishment.

Militarism Beyond Germany: A Continent Embraces Military Might

While Prussian militarism represented its most potent form, militarism was a pervasive force across Europe, albeit manifesting in different intensities and styles. In Britain, for example, militarism, though less overt than its German counterpart, was nonetheless considered indispensable for safeguarding the nation’s vast imperial holdings and extensive trade networks. The Royal Navy, by far the largest and most powerful naval force globally, served as the guardian of vital shipping lanes, international trade routes, and far-flung colonial ports. British land forces were instrumental in maintaining order and enforcing imperial policies throughout India, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, projecting British power across the globe.

British public attitudes toward the military underwent a dramatic transformation during the 19th century. In the preceding century, armies and navies were often regarded as a necessary evil. Their ranks were often filled with individuals from the lower strata of society, while officer positions were sometimes seen as havens for aristocratic failures and ne’er-do-wells. However, the 19th century witnessed a significant shift in the public perception of military service.

Soldiering was increasingly romanticized and portrayed as a noble calling, a selfless act of service to one’s nation. Mirroring the trend in Germany, British soldiers were glorified and idealized in both the press and popular culture. Whether engaged in conflicts in Crimea or stationed in distant colonies, British officers were celebrated as gentlemen and exemplary leaders, while enlisted men were depicted as disciplined, resolute, and prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice ‘for King and Country.’

The idealized image of soldiers as heroes was powerfully encapsulated in Alfred Tennyson’s widely acclaimed 1854 poem The Charge of the Light Brigade. This romanticized view of warfare was further amplified by popular, inexpensive “derring-do” novels that recounted tales of both real and imagined wars, further fueling public enthusiasm for military exploits.

The Arms Race: Militarism’s Inevitable Consequence

Military triumphs, whether in colonial skirmishes or large-scale conflicts like the Crimean War (1853-56) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), only served to elevate the prestige of the military and intensify nationalist fervor. Conversely, military setbacks, such as Russia’s humiliating defeat at the hands of Japan in 1905, or even costly victories, like Britain’s experience in the Boer War (1899-1902), could expose vulnerabilities and amplify calls for military reforms and increased defense spending.

Nearly every major European nation embarked on some form of military modernization and expansion in the late 1800s and early 1900s, driven by a complex mix of nationalistic ambition, imperial rivalry, and a pervasive sense of insecurity. In Germany, military expansion and modernization received enthusiastic endorsement from the newly crowned Kaiser Wilhelm II, who openly proclaimed his desire to secure Germany’s “place in the sun” on the world stage, necessitating a powerful military to achieve this ambition.

In Britain, the arms race was propelled not solely by the monarchy but significantly by public opinion and the influential press. In 1884, prominent newspaperman W. T. Stead published a series of impactful articles arguing that Britain was dangerously unprepared for war, particularly concerning its naval defenses. Pressure groups like the British Navy League, established in 1894, actively campaigned for increased naval construction and personnel. By the early 1900s, the Navy League and influential newspapers were vociferously urging the government to commission more Dreadnoughts – revolutionary new battleships that would redefine naval warfare. A popular and catchy slogan of the era, “We want eight and we won’t wait!” perfectly encapsulated the public’s demand for naval supremacy.

Soaring Military Budgets: Fueling the War Machine

The escalating militarism and the ensuing arms race had a direct and dramatic impact on European military expenditure. Between 1900 and 1914, military spending across the continent skyrocketed. In 1870, the combined military budgets of the six major European powers – Great Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, and Italy – totaled 94 million pounds. By 1914, this figure had quadrupled to a staggering 398 million pounds, demonstrating the immense resources being poured into military buildup. Germany’s defense spending during this period witnessed a colossal increase of 73 percent, dwarfing the increases seen in France (10 percent) and Britain (13 percent), highlighting Germany’s aggressive military expansion.

Russian defense spending also experienced substantial growth, increasing by more than one-third during this period. Russia’s humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 served as a wake-up call, prompting Tsar Nicholas II to initiate a massive rearmament program to modernize and strengthen the Russian military. By the 1910s, approximately 45 percent of the Russian government’s total expenditure was allocated to the armed forces, starkly contrasting with a mere five percent allocated to education, illustrating the prioritization of military might over social development.

With the exception of Britain, every major European power either introduced or expanded conscription policies to bolster the size of their armies. Germany, in the years 1913-14 alone, added a staggering 170,000 full-time soldiers to its army, while simultaneously significantly expanding its navy. In 1898, the German government authorized the construction of 17 new warships, signaling its determination to challenge British naval dominance. Berlin also spearheaded the development of military submarines, and by 1914, the German navy boasted a fleet of 29 operational U-boats, posing a new and significant threat to naval warfare.

This rapid growth in German naval power triggered a wave of alarm and a press frenzy in Britain. London responded decisively to German naval expansion by commissioning 29 new ships for the Royal Navy, further escalating the naval arms race and deepening the atmosphere of mistrust and rivalry.

The following table illustrates the estimated defense and military spending of seven major nations between 1908 and 1913, providing a clear picture of the escalating arms race (figures are in millions of United States dollars):

| Nation | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Britain | $286.7m | $306.2m | $330.4m | $345.1m | $349.9m | $374.2m |

| Germany | $286.7m | $306.8m | $301.5m | $303.9m | $331.5m | $463.6m |

| France | $216m | $236.4m | $248m | $277.9m | $307.8m | $363.8m |

| Russia | $291.6m | $315.5m | $324m | $334.5m | $387m | $435m |

| Italy | $87.5m | $115.8m | $124.9m | $133.7m | $158.4m | $142.2m |

| United States | $189.5m | $199m | $197m | $197m | $227m | $244.6m |

| Japan | $93.7m | $95.7m | $100.2m | $110.7m | $107.7m | $104.6m |

| Source: Jacobson’s World Armament Expenditure, 1935 |

Technological Leaps: Modernizing Warfare for Mass Destruction

This period of intense militarization coincided with a period of rapid technological innovation, leading to significant advancements in the quality and quantity of military weapons and equipment. Drawing lessons from the Crimean War and other 19th-century conflicts, engineers, industrialists, and inventors focused their efforts on developing improvements to military technology, eagerly seeking patents for their innovations.

Perhaps the most transformative advancements were made in heavy artillery, particularly in terms of calibre, range, accuracy, and portability. During the American Civil War (1861-65), heavy artillery had a maximum range of approximately 2,500 meters. By the early 1900s, this range had nearly tripled, dramatically increasing the reach and destructive power of artillery barrages. The development of explosive shells also marked a significant leap forward, greatly enhancing the killing power of each artillery round upon impact. These advancements collectively transformed artillery shelling and bombardments into the most lethal form of weaponry employed in World War I, responsible for an unprecedented level of battlefield carnage.

Machine guns, initially developed in 1881, underwent significant refinements, becoming smaller, lighter, more accurate, more reliable, and possessing dramatically increased rates of fire, with some models capable of firing up to 600 rounds per minute. Small arms technology also advanced significantly. The effective range of a rifle in the 1860s was around 400 meters. In stark contrast, the British Lee-Enfield .303 rifle, a standard issue weapon by the early 20th century, could accurately hit targets at distances exceeding 2,000 meters, revolutionizing infantry combat. Barbed wire, invented in the 1860s, was also readily adopted by military strategists as an effective anti-personnel obstacle, further enhancing defensive capabilities and contributing to the static nature of trench warfare.

While historians continue to debate the precise causes and dynamics of the arms race, there is no doubt that the rapid development and proliferation of new weaponry fundamentally altered the landscape of modern warfare, making it exponentially more destructive. Sir Edward Grey, reflecting on his tenure as British foreign secretary in July 1914, presciently observed:

“A great European war under modern conditions would be a catastrophe for which previous wars afforded no precedent. In old days, nations could collect only portions of their men and resources at a time and dribble them out by degrees. Under modern conditions, whole nations could be mobilised at once and their whole life blood and resources poured out in a torrent. Instead of a few hundreds of thousands of men meeting each other in war, millions would now meet – and modern weapons would multiply manifold the power of destruction. The financial strain and the expenditure of wealth would be incredible.”

In conclusion, militarism’s contribution to the outbreak of World War I can be summarized in these key points:

-

Militarism extended beyond military strength, embedding military values and personnel into civilian governance and societal norms, fostering a belief in military power as essential for national greatness.

-

Germany exemplified extreme militarism, with the Kaiser prioritizing military counsel and the Reichstag lacking real authority over military matters.

-

Experiences from past conflicts, both victories and defeats, fueled militaristic drives and the perceived need for constant military improvement and expansion.

-

Militarism, coupled with technological advancements and industrial growth, ignited a fierce arms race across Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

-

Driven by nationalism and influenced by military advisors, European governments drastically increased military spending, procuring advanced weaponry and expanding their armies and navies to unprecedented levels, ultimately paving the path to global conflict.

Citation information

Title: ‘Militarism as a cause of World War I’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson and Jim Southey

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/militarism/

Date published: September 14, 2018

Date updated: November 15, 2023

Date accessed: December 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.