The question is simple, yet the answer carries a legacy etched in history: a marathon is 26.2 miles long. In kilometers, this iconic distance translates to 42.2 kilometers. For those who prefer even finer precision, we can break it down further:

- 26 miles and 385 yards, equating to approximately 26.218 miles.

- 42,195 meters, which is exactly 42.195 kilometers.

And for runners tackling a slightly shorter challenge, a half marathon measures precisely half of the full marathon distance: 13.1 miles or 21.1 kilometers.

But why this very specific, seemingly arbitrary distance? The answer is a fascinating journey through time, weaving together ancient legends, the birth of the modern Olympics, and a touch of British royalty. Let’s explore the historical path that solidified the 26.2-mile marathon we know and love today.

The Ancient Inspiration: The Battle of Marathon and Pheidippides

The origins of the marathon distance are deeply rooted in the legendary tales of Ancient Greece. While the exact historical accuracy is debated, the captivating story of Pheidippides forms the cornerstone of the marathon mythos.

Pheidippides was a hemerodrome, a highly trained messenger in ancient Greece, tasked with running long distances to deliver critical news. In 490 BC, when Persian forces landed near Marathon, with intentions to advance on Athens, Pheidippides was dispatched on a crucial mission: to seek reinforcements from Sparta.

Popular accounts often mistakenly state that Pheidippides ran from Marathon to Athens (roughly 25 miles) after the battle. However, the more widely accepted version recounts a much longer run before the battle. Pheidippides is said to have journeyed approximately 150 miles across challenging terrain to Sparta to request military assistance. Legend has it that the Spartans, engaged in a religious festival, declined to immediately send troops. Undeterred, Pheidippides then ran back. Whether his return was to Marathon or Athens remains unclear in different accounts.

Meanwhile, the Athenian army, despite being outnumbered, achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Marathon. To prepare for a potential second wave of Persian attack, the army marched swiftly to Athens. They arrived just in time to witness the remaining Persian ships retreating, securing the city’s safety.

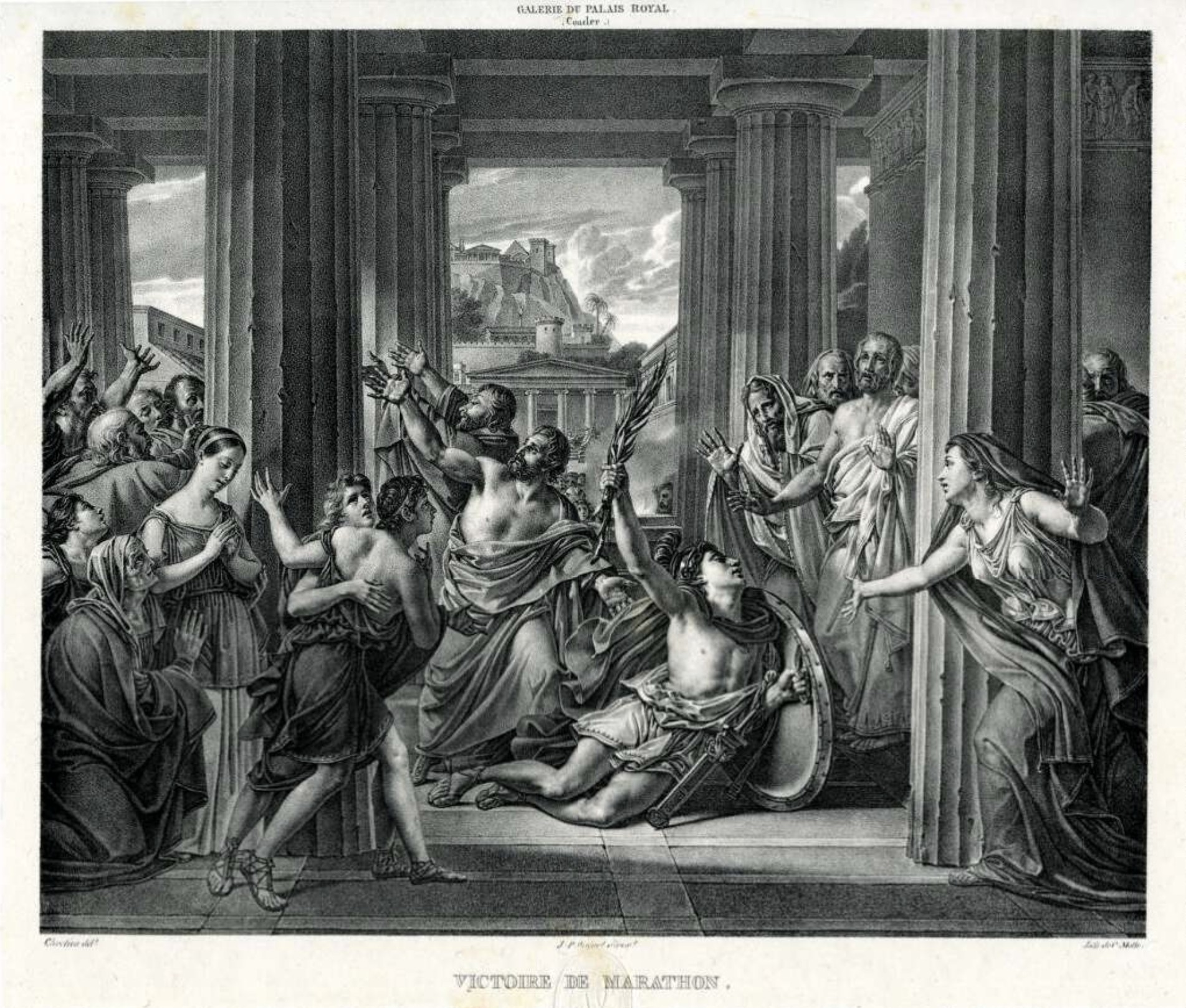

Above: An artist’s depiction of Pheidippides delivering his message © The Trustees of the British Museum

It’s plausible that a messenger was indeed sent ahead to Athens to announce the victory. Conflicting accounts mention names like Pheidippides, Philippides, Thersipus of Erchius, or Eucles as this messenger. The dramatic addition to the legend, of the messenger proclaiming “Nike! Nike! Nenikekiam” (Victory! Victory! Rejoice, we conquer!) before collapsing and dying, is likely a later embellishment, enhancing the narrative’s impact over centuries through poetry and art.

Regardless of the embellishments, the Battle of Marathon and the tale of a heroic run to Athens served as the direct inspiration for the modern marathon race.

An interesting side note: the very name “Marathon” originates from the Greek word for “fennel,” as the area where the battle took place was abundant in this herb.

The 1896 Modern Olympics: Rebirth of a Running Tradition

The ancient Olympic Games, dating back over 2,500 years, were initially a one-day festival, later expanding to five days. These games featured a variety of athletic competitions, including running, throwing, jumping, combat sports, and chariot racing (and notably, athletes often competed in the nude).

Running events in the ancient Olympics included the ‘stadion’ (a sprint of roughly 200m), the ‘diaulos’ (two stadions with a turnaround), the ‘hoplitodromos’ (one or two stadions run in armor), and longer races up to 24 stadions (still under 5km). However, a marathon race as we know it was not part of the ancient Olympic program.

When the concept of a modern, international Olympic Games was revived in 1896, held in Athens, the organizers sought to incorporate elements of Greek heritage. Inspired by the legend of Pheidippides, they proposed a long-distance race from Marathon to Athens. This inaugural Olympic marathon was set at a distance of 40 kilometers (approximately 24.85 miles). Greek water carrier Spyridon Louis emerged victorious, completing the course in 2 hours and 58 minutes, to the jubilant cheers of an estimated 100,000 spectators.

Above: A painting of Spyridon Louis winning the inaugural Olympic Marathon.

The Journey to 26.2 Miles: The 1908 London Olympics

The 1896 Athens Olympics sparked a global revival of marathon running. In 1897, the Boston Marathon, the world’s oldest continuously run marathon, was established, inspired by the Athens race. The first Boston Marathon covered a distance of 24.5 miles (39.4km), with John McDermott winning in 2:55:10.

The marathon distance in the early modern Olympics remained inconsistent. At the 1900 Paris Olympics, the course was 40.26km, and only seven athletes finished in the sweltering heat. The 1904 St. Louis Olympic marathon was marred by controversy and described as ‘the strangest ever,’ with the initial winner disqualified for cheating by hitching a ride for 11 miles of the 40km course.

It was the 1908 London Olympic Games that ultimately cemented the 26.2-mile distance. The marathon route was finalized just days before the event, planned to start at Buckingham Palace and finish at the White City Stadium. Initially intended to be 25 miles, official measurement extended it to 25.5 miles. Then, a significant change occurred: to accommodate the Royal Family, the starting point was moved to the East Terrace of Windsor Castle. This adjustment extended the course to 26 miles to the stadium’s exterior, with runners then completing nearly a full lap of the track, adding approximately 587 yards.

Further adjustments were made for the finish line. While the initial plan was for runners to enter via the Royal entrance, logistical concerns led to a change. Runners were redirected to enter on the opposite side and finish directly in front of the Royal Box. This final alteration resulted in the now-iconic distance of 26 miles and 385 yards, or 26.2 miles.

Above: Dorando Pietri finished first in the 1908 Olympic Marathon but was later disqualified

The 1908 London marathon was also notable for the dramatic story of Dorando Pietri. Pietri, leading the race into the stadium, mistakenly turned the wrong way on the track due to confusion about the clockwise running direction (uncommon at the time). Exhausted and disoriented, he collapsed and was assisted across the finish line, leading to his disqualification. American Johnny Hayes was declared the winner, finishing in 2:55:18.

Interestingly, London was a last-minute replacement host for the 1908 Olympics, stepping in after Rome withdrew due to financial constraints following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 1906. Had the Games remained in Rome, the marathon distance we run today might well be different.

The Official Stamp: 26.2 Miles Becomes the Standard

Between the 1896 and 1920 Olympics, the marathon distance varied across the seven Games, reaching its longest at 42.7km in the 1920 Antwerp Olympics. In 1921, the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF), now World Athletics, officially standardized the marathon distance at 26.2 miles (42.2km). However, the precise reasons for choosing the 1908 London Olympic distance as the standard remain somewhat unclear.

From the 1924 Paris Olympics onward, all Olympic marathons adhered to the 26.2-mile standard. In 1924, the Boston Marathon also adjusted its course, moving the starting line to Hopkinton to conform to the official 26.2-mile distance. This marked a century milestone in 2024: 100 years of runners globally embracing the precise 26.2-mile challenge for the love of the sport.

For a deeper dive into the myths and legends surrounding the marathon distance, you can listen to The Running Channel podcast featuring Andy, Sarah, and Rick discussing the fascinating history.