In the vast landscape of the English language, a fascinating phenomenon emerges: the majority of words carry not a singular, monolithic meaning, but a spectrum of interpretations. This inherent characteristic of language, known as semantic ambiguity, manifests in two primary forms: homonymy, where words possess unrelated meanings (like “bank” referring to a financial institution or the side of a river), and polysemy, where words have multiple related senses (such as “paper” used for research documents or wrapping material). For decades, researchers have been captivated by the intricate ways in which the human mind navigates this semantic richness, seeking to understand How Meaning is constructed and processed when words themselves are multifaceted.

This article delves into the compelling field of semantic ambiguity, focusing on how meaning is deciphered from words that inherently carry multiple potential interpretations. While previous reviews have laid the groundwork in understanding semantic ambiguity, recent studies have shifted focus to the critical role of semantic similarity between these multiple meanings. This exploration is essential to understanding the nuances of language comprehension and how meaning is dynamically constructed in our minds. We will analyze current research, highlighting both consistent and conflicting findings, and explore how key factors such as semantic relatedness, frequency of meaning, task demands, timing, and sensory modality influence the intricate process of ambiguous word processing. Furthermore, we will discuss these findings in the context of contemporary parallel distributed processing (PDP) models, and consider how experience-based models contribute to a more complete understanding of semantic ambiguity resolution and, ultimately, how meaning emerges from language.

Semantic Ambiguity

Semantic Ambiguity

The Pervasiveness of Semantic Ambiguity and Its Impact on Meaning Comprehension

Semantic ambiguity is not a linguistic anomaly, but rather a fundamental aspect of language. A significant proportion of words we use daily are semantically ambiguous, capable of evoking different senses or meanings depending on context. This ubiquity naturally raises a crucial question for cognitive science: how meaning is effectively extracted and resolved from these ambiguous linguistic units? Understanding this process is paramount to unraveling the complexities of human language comprehension.

Early investigations into semantic ambiguity centered on the activation of multiple meanings. Researchers were keen to discover whether all possible meanings of an ambiguous word are activated upon encountering it, and if so, how meaning selection is influenced by factors such as contextual cues, the frequency with which each meaning is used, and the strength of contextual biases. These initial studies sought to map out the initial stages of how meaning emerges from ambiguous words.

Research has consistently demonstrated the interplay of context, meaning frequency, and contextual strength in resolving lexical ambiguity. However, more recent investigations have highlighted a crucial dimension often overlooked in earlier work: the semantic similarity between the various meanings or senses of ambiguous words. This shift in focus has led to a deeper appreciation of how meaning is not only selected but also shaped by the inherent semantic relationships within ambiguous words themselves.

Distinguishing Homonymy and Polysemy: Different Pathways to ‘How Meaning’ is Understood

A key distinction in understanding semantic ambiguity lies in differentiating between homonymy and polysemy. Homonyms are words that share the same written and spoken form but possess meanings that are entirely unrelated. Think of “bat,” which can refer to a flying mammal or a piece of sports equipment. In contrast, polysemes are words that also share a form but have multiple senses that are related in some way. “Paper,” as mentioned earlier, is a prime example; its senses, while distinct, are conceptually linked. Recognizing this difference is crucial to understanding how meaning resolution operates differently for these two types of ambiguity.

The majority of semantically ambiguous words in English are, in fact, polysemous. This prevalence underscores the importance of studying polysemy to fully grasp how meaning is constructed and understood in everyday language use. In this review, we will adhere to a consistent terminology: “meanings” will refer to the distinct interpretations of homonyms, while “senses” will denote the multiple, related interpretations of polysemous words. This distinction allows for a more precise analysis of how meaning processing differs between these categories.

Within polysemy, further classifications exist that shed light on how meaning is structured. Metonymy, for instance, occurs when different senses of a polysemous word are literally related. Consider “chicken,” which can denote the living animal or its meat. These senses are linked through a clear, real-world relationship. Other types of metonymy include container/contents relations (“glass” for the object or its contents) and part/whole relationships (synecdoche, like “wheels” representing a car). These “regular” polysemes exhibit predictable relationships between their senses, influencing how meaning is accessed and interpreted.

In contrast, “irregular” polysemes display less predictable connections between their senses. Metaphorical polysemy, for example, involves one literal sense and another figurative sense, as in “eye” referring to a body part or the center of a storm. These metaphorical senses are less concretely related, potentially impacting how meaning is processed and understood compared to metonymous polysemes. The degree of semantic similarity between senses appears to be a critical factor in how meaning is managed in polysemous words.

Categorizing Ambiguity: Linguistic and Psychological Approaches to ‘How Meaning’ is Defined

From a linguistic perspective, the classification of ambiguous words into polysemes and homonyms often relies on rule-based systems that analyze the relationships between different meanings or senses. These rules attempt to formally define how meaning connections determine category membership.

Psychologically, however, ambiguity categorization has also been approached through dictionary definitions. Words with separate entries are often classified as homonyms, while words with multiple definitions under a single entry are considered polysemes. This dictionary-based approach provides a practical method for researchers to categorize words and explore how meaning distinctions are reflected in lexicographical organization. Furthermore, dictionary order has been used as a proxy for meaning frequency, with earlier definitions assumed to be more frequent.

Another psychological approach employs norms derived from participant responses. In this method, individuals generate associations for words, and subsequent participants rate the semantic similarity of these associations. This normative approach offers a more data-driven way to assess how meaning relatedness is perceived and categorized, moving beyond dictionary definitions.

While categorical distinctions are useful for experimental design and theoretical frameworks, it’s important to acknowledge that semantic ambiguity exists on a continuum of semantic similarity. Homonyms and polysemes are not necessarily discrete categories but rather points along this spectrum. Recent statistical advancements allow for the analysis of ambiguity as a continuous variable, capturing the nuanced degrees of semantic relatedness and providing a more ecologically valid perspective on how meaning ambiguity is processed. Homonyms reside at one end of this continuum, metonymous polysemes at the other, with metaphorical polysemes occupying a middle ground.

Recent Research: Unpacking ‘How Meaning’ is Processed in Ambiguous Words

Contemporary research has increasingly focused on the different types of semantic ambiguity and the degree of semantic similarity between word meanings. These studies are crucial for understanding how meaning processing varies across different forms of ambiguity. Some studies have revealed a processing advantage for polysemous words in lexical decision tasks, suggesting that related senses facilitate word recognition. Conversely, homonyms have sometimes been found to exhibit a processing disadvantage, particularly in tasks demanding meaning specification.

However, the findings are not always consistent. Mixed results persist, and the underlying reasons for these processing advantages and disadvantages remain a subject of ongoing debate. This review will critically examine recent studies on semantic ambiguity effects, aiming to identify potential factors contributing to these inconsistencies and further illuminate how meaning is processed under conditions of ambiguity.

Study Selection Criteria

To provide a focused and current analysis, this review concentrates on behavioral and electrophysiological studies published from 2001 onwards. This temporal focus acknowledges the extensive body of literature prior to 2001 while highlighting the advancements in understanding semantic ambiguity in recent decades. Studies included were identified through searches on Google Scholar and PsychINFO using keywords such as “homonymy,” “polysemy,” “semantic ambiguity,” and “lexical ambiguity.” Furthermore, the review prioritizes studies that explicitly examine different types of ambiguous words, particularly polysemes and homonyms, to delve into how meaning processing diverges across these categories.

Review Outline: Exploring the Landscape of ‘How Meaning’ Research

This review will systematically explore the consistent and inconsistent patterns emerging from recent research on semantic ambiguity, aiming to clarify how meaning is processed and represented in the context of ambiguity. We will begin by discussing key aspects of semantic ambiguity processing and representation, then move into a detailed review of recent behavioral and electrophysiological studies, summarized in Table 1.

The review will address the inconsistencies in reported ambiguity effects by examining potential contributing factors. These include the types of words used, the semantic similarity of word meanings, the nature of responses required in tasks (e.g., “yes” vs. “no”), the type of task itself, the modality of presentation (auditory or visual), timing parameters, and the types of distractor items (foils) employed. By analyzing these factors across studies, we aim to understand how meaning processing is modulated by experimental design choices.

Ultimately, the discussion will explore how these findings contribute to our understanding of models of semantic ambiguity. We will specifically consider how parallel distributed processing (PDP) models and experience-based models can inform a more comprehensive understanding of semantic ambiguity resolution and how meaning is dynamically constructed from ambiguous linguistic input.

(Table 1 as provided in the original article would be inserted here)

Theoretical Models of Semantic Ambiguity: Frameworks for Understanding ‘How Meaning’ is Organized

Researchers have framed the effects of ambiguity within the context of lexical storage and access, seeking to understand how meaning representations are organized and retrieved. Both polysemous and homonymous words present multiple senses or meanings, differing primarily in the semantic relationships between them. Two main theoretical frameworks attempt to explain how meaning is represented for ambiguous words: the Separate Entry Model and the Single Entry Model.

Separate Entry Model: Distinct Representations for Each Meaning

The Separate Entry Model posits that each meaning or sense of an ambiguous word, regardless of its relatedness to other meanings, is stored as a distinct entry in the mental lexicon. This model suggests that for both polysemes and homonyms, each interpretation is linked to a single orthographic and phonological form but maintained as a separate representation. This perspective emphasizes the multiplicity of how meaning is encoded, suggesting independent pathways for each interpretation.

Single Entry Model: Shared Representations for Related Senses

In contrast, the Single Entry Model, particularly relevant to polysemous words, proposes that highly related senses are stored together within a single lexical entry. This model suggests a more economical representation for polysemes, emphasizing the shared semantic core that underlies their various senses. However, for homonyms, whose meanings are unrelated, the Single Entry Model aligns with the Separate Entry Model, suggesting distinct storage for each meaning. This model directly addresses how meaning relatedness influences lexical organization.

Within the Single Entry Model for polysemes, two variations exist. One suggests that senses share a “core meaning,” with individual senses generated through rules or relationships applied to this core. The other proposes that polysemous word representations are underspecified, with distinct senses derived “online” during processing. While the representation of polysemes is debated, a general consensus exists that homonym meanings are stored separately, reflecting their accidental co-occurrence under a single word form. These models provide contrasting perspectives on how meaning multiplicity is managed in the lexicon.

Computational Models: PDP Approaches to ‘How Meaning’ is Simulated

Computational models, particularly those within the parallel distributed processing (PDP) framework, offer a powerful tool for investigating ambiguity representation and processing. These models allow researchers to simulate how meaning emerges from neural networks and test specific hypotheses about lexical organization. PDP models can integrate orthographic and semantic information, providing a mechanistic account of word processing.

In PDP models, layers of interconnected nodes represent word features, such as orthography, phonology, and semantics. For ambiguous words, a single orthographic pattern maps to multiple semantic patterns, whereas unambiguous words exhibit a one-to-one mapping. The network is trained to learn these mappings, and its performance in processing different word types is analyzed.

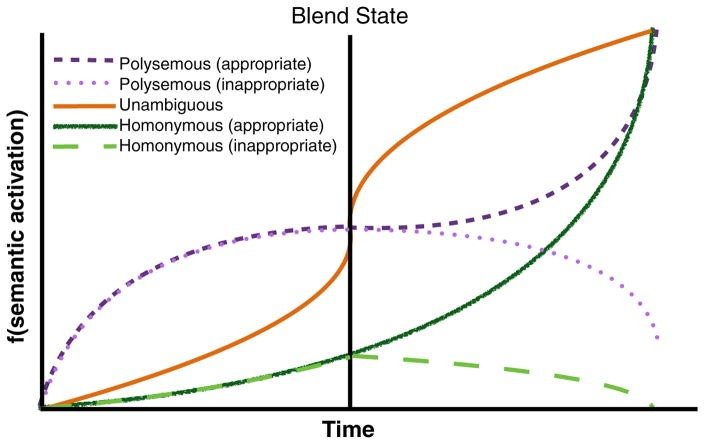

After training, the network reaches a state of stability, settling into “attractor basins.” These basins represent points of attraction shaped by connection strengths. A shallow attractor basin could represent a core meaning shared by polysemous senses, aligning with the Single Entry View. Conversely, a deep attractor basin could represent a specific meaning, consistent with the Separate Entry View. PDP models thus offer a dynamic way to explore how meaning is represented and accessed, simulating the cognitive processes involved in ambiguity resolution.

Behavioral Studies: Investigating ‘How Meaning’ is Processed in Different Tasks

Behavioral studies provide crucial empirical data for understanding how meaning is processed in ambiguous words. These studies often employ tasks that vary in their semantic demands, ranging from less semantically engaging tasks like lexical decision to more semantically intensive tasks such as semantic judgments. Comparing performance across these tasks reveals how ambiguity effects are modulated by task demands and provides insights into the time course of how meaning activation unfolds.

Less Semantically Engaging Tasks: Lexical Decision and Early ‘Meaning’ Access

Tasks like lexical decision, where participants decide if a presented string of letters is a real word, are considered less semantically engaging. Accurate performance in lexical decision primarily relies on orthographic or phonological recognition, potentially minimizing the need for full semantic activation to determine how meaning is accessed initially.

Early lexical decision studies often reported an advantage for ambiguous words, with faster response times compared to unambiguous words. However, these early studies often did not differentiate between polysemes and homonyms, overlooking the role of semantic similarity in how meaning processing varies across ambiguity types.

Pioneering work by Klepousniotou (2002) and Rodd et al. (2002) began to disentangle the effects of polysemy and homonymy in lexical decision. Rodd et al. (2002) demonstrated that the previously reported “ambiguity advantage” might be specific to polysemous words. They found that words with more senses (polysemes) were processed faster, while words with more meanings (homonyms) were processed slower, suggesting different mechanisms for how meaning is accessed and processed in these two types of ambiguity. The use of pseudohomophones as non-words in these tasks may enhance semantic processing demands, potentially amplifying ambiguity effects on how meaning is activated.

Intriguingly, Rodd et al. (2002) found similar patterns in auditory lexical decision, even when using pronounceable non-words instead of pseudohomophones. This finding challenges the notion that difficult non-words are necessary to elicit ambiguity effects in lexical decision, suggesting that auditory processing itself may inherently increase semantic activation and influence how meaning is processed.

These studies suggest that the “ambiguity advantage” may not be a general phenomenon but rather a polysemy advantage, indicating that related senses facilitate word recognition, while unrelated meanings might hinder it. This points to a crucial role for semantic relatedness in how meaning influences lexical access.

Further refining this distinction, Klepousniotou and Baum (2007) investigated different types of polysemes: metaphorical and metonymous. They found that metonymous polysemes exhibited a processing advantage in both auditory and visual lexical decision tasks, suggesting a special status for these words with highly related senses in how meaning is accessed and processed. Metaphorical polysemes, however, did not consistently show this advantage, indicating that the degree of semantic relatedness within polysemes significantly impacts how meaning facilitates or hinders lexical processing.

However, not all studies consistently find a disadvantage for homonyms. Lin and Ahrens (2010) reported an overall ambiguity advantage for both homonyms and metaphorical polysemes in Mandarin Chinese lexical decision, challenging the idea that the advantage is limited to polysemes with highly related senses and raising questions about cross-linguistic variations in how meaning ambiguity is processed.

Inconsistent findings also emerge in Japanese lexical decision tasks. Hino et al. (2006) found an overall ambiguity advantage but no specific polysemy advantage, while Hino et al. (2010) found a polysemy advantage only when using Kanji characters as non-words, suggesting that non-word type and script manipulations can influence how meaning processing is assessed in lexical decision. These inconsistencies highlight the complexity of isolating specific factors that contribute to ambiguity effects and how meaning is processed in different experimental contexts.

To address the issue of item-level differences between word types, Rodd et al. (2012) employed a novel training paradigm. They taught participants new meanings to previously unambiguous words, creating artificial polysemes and homonyms using the same base words. This design eliminated stimulus list confounds and allowed for a more controlled investigation of how meaning similarity affects processing. They found that participants learned and recalled related meanings more readily than unrelated meanings, and lexical decision responses to trained related-meaning words were faster, providing strong evidence that semantic similarity facilitates word recognition and how meaning representations are formed.

More Semantically Engaging Tasks: Semantic Judgments and Deeper ‘Meaning’ Activation

Tasks such as sense judgment, semantic categorization, and semantic relatedness tasks are considered more semantically engaging, requiring deeper semantic processing and specific meaning activation to achieve accurate performance. These tasks offer insights into how meaning is selected and processed when semantic demands are increased.

Klepousniotou (2002) used primed lexical decision and found that metonymous polysemes showed a greater priming effect compared to homonyms, further supporting the idea that semantic relatedness facilitates how meaning is accessed and processed in polysemes.

Hino et al. (2002) used a semantic categorization task and found an ambiguity disadvantage, with slower responses to ambiguous words. They argued that semantic tasks require “settling” on a specific meaning, and the presence of multiple meanings in ambiguous words slows down this selection process, impacting how meaning is resolved for categorization decisions.

Pexman et al. (2004) investigated ambiguity effects in a relatedness judgment task. They found an ambiguity disadvantage only in “yes” trials, where one meaning of the ambiguous word was related to the target word. They proposed a Decision System Account, suggesting that response competition between multiple meanings in “yes” trials leads to the disadvantage, rather than semantic activation differences, highlighting how meaning ambiguity impacts decision-making processes.

However, Hino et al. (2006) found ambiguity disadvantages in semantic categorization even in “no” trials, particularly for homonyms, and polysemy advantages for polysemes compared to homonyms. They attributed these effects to the breadth of semantic categories, suggesting that broader categories increase decision complexity and amplify ambiguity effects on how meaning is processed in categorization tasks.

Klein and Murphy (2001) used a sense judgment task and found a consistency effect, where judgments were faster when word pairs shared the same sense. They argued that this effect suggests separate storage of polysemous word senses, challenging the Single Entry Model and raising questions about how meaning relatedness influences lexical representation. However, Brown (2008), using a similar sense judgment task but focusing on verbs, found a polysemy advantage and a linear trend of increasing semantic similarity leading to faster and more accurate responses, suggesting that the continuum of semantic similarity plays a crucial role in how meaning is processed in semantic tasks.

Klepousniotou et al. (2008) also used a sense judgment task and found that polysemous word pairs with highly overlapping senses were processed faster, emphasizing the importance of sense overlap in how meaning is accessed and processed in semantic judgments.

Foraker and Murphy (2012) used self-paced reading and eye-tracking to investigate polysemy processing in sentence contexts. They found that dominant senses were processed faster, and semantic similarity interacted with dominance, suggesting that both factors influence how meaning is resolved in natural language comprehension.

Armstrong and Plaut (2008, 2011) proposed the Settling Dynamics Account, using PDP models to simulate ambiguity effects. They argued that the type of ambiguity effect depends on the “semantic precision” required by the task. Less semantically engaging tasks elicit polysemy advantages, while more semantically engaging tasks elicit homonym disadvantages, suggesting that the time course of semantic activation and task demands interact to determine how meaning ambiguity effects manifest. Their behavioral studies manipulated non-word difficulty and stimulus quality in lexical decision, finding evidence for both polysemy advantages and homonym disadvantages depending on task conditions, supporting their Settling Dynamics Account of how meaning processing changes with task demands.

Electrophysiological and Neuroimaging Studies: Unveiling Neural Correlates of ‘How Meaning’ is Processed

Electrophysiological methods like ERPs and neuroimaging techniques like MEG provide temporally sensitive and spatially informative data to complement behavioral findings and further elucidate how meaning is processed in ambiguous words. These methods allow researchers to examine neural responses associated with different stages of lexical and semantic processing, offering a more direct window into brain activity related to how meaning is constructed.

Pylkkänen et al. (2006) used MEG and a sense judgment task, examining the M350 component, thought to reflect lexical access. They found earlier M350 peaks for related polysemous pairs but later peaks for related homonymous pairs, suggesting distinct neural signatures for how meaning is processed in polysemes and homonyms and supporting the Single Entry Model for polysemes.

Beretta et al. (2005) also used MEG and lexical decision, examining the M350. They found earlier M350 peaks for polysemous words compared to homonyms, mirroring behavioral RT effects and further supporting the Single Entry Model for polysemous word representation and providing neural evidence for how meaning processing differs between ambiguity types.

Klepousniotou et al. (2012) used ERPs and primed lexical decision, examining the N400 component, an indicator of semantic integration. They found different N400 priming effects for homonyms and different types of polysemes, suggesting distinct neural processing pathways for how meaning is accessed and integrated for various forms of semantic ambiguity. They also found hemispheric differences in N400 effects for different types of ambiguous words, hinting at different neural generators contributing to how meaning processing varies across ambiguity types.

Discussion: Processing Issues and the Time Course of ‘How Meaning’ Activation

The inconsistent findings in the semantic ambiguity literature may stem from several factors. Stimulus variability across studies, including word lists, non-word types, and language differences, can influence results. Categorical approaches to ambiguity classification may oversimplify the continuous nature of semantic similarity and mask subtle but important differences in how meaning is processed. Meaning frequency and part-of-speech variations across studies also contribute to the complexity of interpreting results.

Despite inconsistencies, patterns emerge. Semantic similarity consistently facilitates word recognition, while semantic dissimilarity can hinder it. Task demands and timing play a crucial role, with less semantically engaging tasks often showing polysemy advantages and more semantically engaging tasks sometimes revealing homonym disadvantages. These patterns underscore the importance of considering task demands and semantic relatedness when investigating how meaning ambiguity is processed.

PDP models, like the Settling Dynamics Account, provide a framework for understanding these varying effects. Rodd et al. (2004) proposed a model where polysemes develop shallow attractor basins and homonyms develop deep attractor basins, explaining the processing differences based on attractor dynamics and how meaning representations are shaped in the network. Armstrong’s (2012) Settling Dynamics Account further elaborates on this, suggesting that the time course of semantic activation and the level of semantic precision required by the task determine the type of ambiguity effect observed and how meaning processing unfolds over time.

Discussion: Representational Issues and Lexical Organization of ‘How Meaning’

While evidence suggests polysemes and homonyms are processed differently, the question of their representation in the mental lexicon remains. A consensus exists that homonym meanings are stored separately. However, the representation of polysemes is debated. The polysemy advantage in some tasks suggests that polysemous senses may be stored together, potentially within a single lexical entry, reflecting a more integrated representation of how meaning is structured for polysemes. However, alternative explanations, such as early semantic effects in PDP models, also need consideration.

Static representations of the lexicon, assumed in many theories, may not fully capture the dynamic nature of how meaning is acquired and modified. Learning new meanings and interpretations can alter word representations. Rodd et al. (2012) demonstrated the plasticity of word representations by showing that training new meanings to unambiguous words can induce ambiguity effects, highlighting the dynamic and adaptable nature of how meaning representations. Experience-based models offer a promising avenue for understanding how meaning representations evolve with learning and experience.

General Discussion: Towards a Comprehensive Model of ‘How Meaning’ is Resolved

Semantic ambiguity significantly influences language processing. Different types of ambiguous words are processed differently, and semantic similarity plays a crucial role in ambiguity resolution and how meaning is accessed and understood. Polysemes are generally processed more easily than homonyms, and within polysemes, metonyms often show processing advantages over metaphors, highlighting the nuanced effects of semantic relatedness on how meaning processing varies across ambiguity types.

The findings suggest that early ambiguity advantage effects may primarily reflect polysemy advantages, emphasizing the facilitative role of related senses in word recognition and how meaning processing benefits from semantic coherence. Future research should consider semantic similarity as a continuum and explore its full range of effects on how meaning processing. Examining ambiguity effects across diverse tasks and considering the time course of processing, both within tasks and over learning, will further refine our understanding of how meaning ambiguity is resolved.

Experience-based models, in conjunction with PDP frameworks, offer promising avenues for future research. Instance-based accounts, which emphasize the role of individual word encounters in shaping representations, can complement PDP models like the Settling Dynamics Account to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how meaning is learned, processed, and represented in the face of semantic ambiguity.

Ultimately, understanding how meaning is extracted from ambiguous words is crucial for unraveling the complexities of human language comprehension. Future research that embraces the dynamic nature of semantic representation, considers the continuum of semantic similarity, and integrates computational and experience-based perspectives will be essential to building a more complete and nuanced model of semantic ambiguity resolution and how meaning is constructed in the human mind.

Acknowledgments

(As per original article)

Contributor Information

(As per original article)

References

(References as provided in the original article would be listed here, formatted in markdown for links if possible)