Navigating the complexities of “How Much Is Unemployment In California” requires a deep dive into the state’s economic landscape. HOW.EDU.VN provides expert insights, offering solutions to understand the current unemployment rates and the factors influencing them. By examining the state’s policies and economic indicators, we aim to clarify the financial support available and its impact on California’s workforce. Gain a clearer perspective on unemployment benefits, job market trends, and economic stability in California.

1. Understanding California’s Unemployment Insurance System

The joint federal-state Unemployment Insurance (UI) system was created after the Great Depression to protect workers and families from income loss. It also boosts the economy during downturns by supporting consumer demand and ensuring job seekers don’t take substandard jobs that could lower wages and working conditions.

Economists now recognize that UI helps improve job matches, enhance the labor market, and helps employers find workers with the right skills, improving their efficiency. By giving workers time to find better jobs, UI contributes to higher wages and job satisfaction. However, California’s low benefits and exclusions weaken UI’s ability to fulfill these functions.

2. The Critical Role of Unemployment Benefits

Unemployment benefits remain crucial for recipients. In 2022, UI prevented over 400,000 people nationwide, including 116,000 children, from poverty. Even for those not facing poverty, these benefits reduce hardship and improve household well-being, including financial stability and mental health.

California’s benefits haven’t increased in nearly two decades. The average benefit was only $368.53 a week in 2023, which isn’t enough for Californians, especially those with low incomes, to meet the rising cost of living while seeking employment. A worker losing a full-time minimum wage job (at $16.90 per hour in Los Angeles County) receives just $1,465 in monthly unemployment benefits, falling $69 short of covering rent for a studio in Los Angeles at Fair Market Rent. California’s UI benefits are significantly lower than other Western states, such as Washington ($703.79 per week), Oregon ($543.81 per week), Nevada ($450.70 per week), and Hawaii ($613.30 per week).

3. Disparities in Unemployment Insurance Benefits

California’s minimum UI benefit of $40 per week is among the nation’s lowest, below the minimum benefits of 29 other states. Washington’s minimum benefit is seven times greater ($295 per week), while Arizona’s is $200 per week, and Oregon’s is $171. Additionally, 12 states offer dependent allowances, providing a weekly supplement for workers with children and other dependents. California offers no additional support to unemployed parents and other workers supporting dependents.

4. How Low UI Benefits Worsen Racial and Gender Inequities

Low UI benefits can be particularly harmful for workers of color, including American Indian, Black, Latinx, and Pacific Islander Californians, especially women. These groups are overrepresented in low-paying jobs due to structural racism and sexism. Since benefit levels are based on prior wages, low-paid workers receive lower UI benefits. Workers who lived paycheck to paycheck face greater hardship trying to cover expenses on benefits that are a small fraction of their paycheck. Workers of color typically have fewer financial resources other than UI benefits due to systematic exclusion from wealth-building opportunities over generations.

5. The Economic Impact of Unemployment Insurance

California’s low benefit levels also undermine UI’s ability to combat recessions. A strong UI system is one of the most effective tools to promote economic recovery. The International Monetary Fund found that each dollar paid in UI benefits during the pandemic generated $1.92 of economic growth as workers and their families continued to spend on basic necessities.

This impact was achieved because the federal government expanded UI benefits during the pandemic. A $600 a week supplement to regular state UI benefits early in the pandemic (later $300 a week) ensured unemployed workers could keep spending money, supporting local businesses. Expanded federal benefits also helped California job seekers and families meet expenses better than they could with the state’s regular UI benefits.

Federal pandemic programs also expanded UI eligibility to self-employed workers, caregivers, misclassified independent contractors, part-time workers, and many underpaid workers typically excluded from California’s regular UI system. By expanding the share of unemployed workers receiving support, federal pandemic programs further improved UI’s ability to stabilize the economy.

6. Excluded Workers and the Need for Inclusive Policies

More than 1 million undocumented workers, representing over 6% of California’s workforce, were notably excluded from the UI benefit expansions. California created a Disaster Relief Assistance for Immigrants (DRAI) program to provide limited, one-time financial assistance to unemployed immigrants ineligible for UI benefits. However, the support was inadequate, with researchers finding that unemployed citizen workers in California were eligible for up to 20 times more aid than the state’s undocumented workers in the first year of the pandemic. Workers on strike are also excluded from UI benefits, even though they miss paychecks and risk hardship for exercising their right to collective action. California should consider expanding UI benefits to striking workers, like New York and New Jersey.

Now that federal and state emergency programs have expired, Californians are left with a UI system that inadequately supports job seekers and excludes many of them. California’s UI system is unprepared for the next economic shock or crisis. With growing concerns that artificial intelligence could displace large numbers of workers, a strong UI system is needed more than ever to support displaced Californians.

7. The Necessity of Adequate UI Financing

Unemployment insurance is funded by state and federal payroll taxes. The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) funds UI administrative costs and special programs, while the State Unemployment Tax Act (SUTA) tax, imposed by states, pays for UI benefits and repays federal loans to the state’s UI trust fund. SUTA tax revenues are deposited into a trust fund held for each state by the US Treasury.

State unemployment insurance benefits are paid from each state’s trust fund. If states lack sufficient funds, they can take out a federal loan. California and 21 other states did this during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the federal government fully paid for expanded UI benefits during the pandemic, California still faced a record $35 billion in costs for regular UI benefits and currently has a trust fund debt of $19.8 billion.

8. Addressing the Structural Deficit in California’s UI System

The pandemic’s extraordinary costs are just the latest manifestation of a structural deficit in California’s UI financing system. In January 2020, before the pandemic, California had the most underfunded UI system of any state. Even today, with a relatively low unemployment rate around 5%, California doesn’t raise enough revenue to pay for current UI benefits, much less pay down its trust fund debt.

In addition to regular SUTA taxes, California employers pay a 15% tax surcharge to repay the trust fund loan, but this isn’t enough to reduce the principal. The Employment Development Department projects that the outstanding federal UI loan balance will grow to nearly $22 billion in 2025. California must overhaul its UI revenue system to support unemployed workers and the economy, pay down its debt, and build a reserve for future economic downturns.

9. The Cost of Failing to Modernize UI Financing

California’s underfunded UI system imposes steep costs across the state. Job seekers struggle to get by on low UI benefits, and many jobless workers are excluded. Meager benefits may not be enough to power the state’s economic recovery in the next downturn. The interest on the trust fund debt has traditionally been paid from the state’s general fund, so all California residents ultimately pay a price.

Due to rising interest rates, California owed $484 million in interest on UI debt in 2024, during a significant, multi-year budget shortfall. Although California used internal borrowing to cover the 2023 interest payment, there were fewer options in 2024, and the state’s final budget agreement covered most of the interest payment ($384 million) with General Fund dollars, diverting resources from other priorities like health care, child care, affordable housing, and environmental protection. California will continue to owe interest every year it maintains trust fund debt, significantly reducing funding available for other critical priorities.

Employers may worry about increased UI taxes in a modernized system, but they also face a direct tax penalty if no action is taken. In addition to the surcharge to repay the loan, California employers will face a reduction in the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) tax credit, effectively hiking their taxes as long as the trust fund debt continues to go unpaid.

10. The Role of the Taxable Wage Base in UI Financing

Failure to raise revenue is central to California’s UI financing crisis. State policymakers have been hesitant to require employers to contribute the funds needed for a strong and effective UI system. As a result, California taxes employers on only the first $7,000 of each employee’s pay.

10.1. Understanding the Taxable Wage Base

State unemployment benefits are financed through state payroll taxes paid by employers. The amount employers pay depends on the tax rate and the taxable wage base. The tax rate is determined for each employer based on schedules outlined in state law. The rate for a particular employer is applied to a taxable wage base equal to each of their employee’s first $7,000 in annual earnings to determine how much tax the employer owes.

For example, new employers are assigned a state payroll tax rate of 3.4%. If a new employer has three employees all earning $40,000 annually, the employer would calculate the payroll tax they owe by multiplying 3.4% by $7,000 for each employee ($238), for a total annual tax of $714 for all three employees. If the taxable wage base were higher, say $21,000, the same amount of revenue could be raised with a much lower tax rate (1.1%) because a greater proportion of each worker’s wages would be subject to taxation. Alternatively, by maintaining a 3.4% tax rate, the higher taxable wage base would raise three times as much revenue ($2,142 for all three employees).

When comparing state payroll taxes across states, it’s important to consider both the tax rate and the taxable wage base. A state with relatively high tax rates does not necessarily result in employers in that state paying more in taxes than states with lower tax rates. For example, a 5.7% rate would generate a tax of $400 if applied to a base of $7,000. But a much lower rate of 3.8% would generate twice as much tax ($800) if applied to a base of $21,000.

10.2. The Impact of a Low Taxable Wage Base

This low fixed amount, the taxable wage base, not only raises inadequate revenue but raises it inequitably. The low taxable wage base means that California taxes a higher proportion of the wages of low-paid workers and imposes the highest effective tax rates on small businesses while failing to keep up with wage growth and taxing a far smaller share of wages than most other states. Raising the taxable wage base and indexing it to the state’s average wages is essential to strengthen the UI system. Wages have increased significantly over the last 40 years, yet California’s taxable wage base has remained fixed, lagging further and further behind. While the state’s taxable wage base of $7,000 was equivalent to full-time wages at the federal minimum wage in 1982, it was less than three months of full-time work at the minimum wage in 2022 in California. By 2022, California’s effective UI tax rate was less than half of what it had been in 1980, as the figure below illustrates.

California’s UI financing system disproportionately taxes the employers of low-paid and part-time workers because the state’s taxable wage base is so low. Take, for example, employers subject to a state UI tax rate of 3.1%, which is the average rate paid by employers in 2023. Since most workers earn more than the state’s taxable wage base of $7,000, employers effectively pay $217 in state UI taxes per worker. But this represents a much larger share of employers’ labor costs for low-paid and part-time workers. For instance, $7,000 amounts to 1.3% of the earnings paid to half-time minimum wage workers, compared to 0.7% of the earnings paid to full-time minimum wage workers and just 0.2% of the earnings of workers paid three times the minimum wage, as the figure below shows. Researchers find that this creates disincentives to hire part-time workers in the first place, leading to fewer employment opportunities, which would impact workers who benefit from the flexibility of part-time work or who rely on additional earnings to make ends meet. Raising the taxable wage base would help to address these inequalities.

Small businesses also bear a disproportionate tax burden as a result of California’s low taxable wage base for UI.

10.3. Comparing California to Other States

Raising California’s taxable wage base is not unrealistic. In fact, 94% of US states already have a higher taxable wage base than California, including Washington State with a taxable wage base of $68,500 in 2024, Oregon ($52,800), Nevada ($40,600) and Hawaii ($59,100). These states not only tax a much higher share of payrolls than California, but their wage base is indexed to the state’s average weekly wage so that it adjusts automatically each year as wages rise, providing far more reliable financing than California’s low fixed rate. As the figure below shows, businesses in California actually pay taxes on a smaller share of wages than any other state, with just 8% of average annual earnings taxed. California’s low, fixed taxable wage base leads it to raise far less UI revenue than the state needs.

11. Moving Towards Forward Financing and Reforming Experience Rating

Raising and indexing California’s taxable wage base is essential for adequate UI financing, but it alone will not sustainably fund the system because of the structurally flawed mechanism that determines UI tax rates in California. California has seven employer contribution rate schedules that increase state UI tax rates when the state’s UI trust fund balance is low and reduce rates when the trust fund has more funding. This “pay-as-you-go” mechanism is meant to increase revenues when needed, but it produces two perverse outcomes.

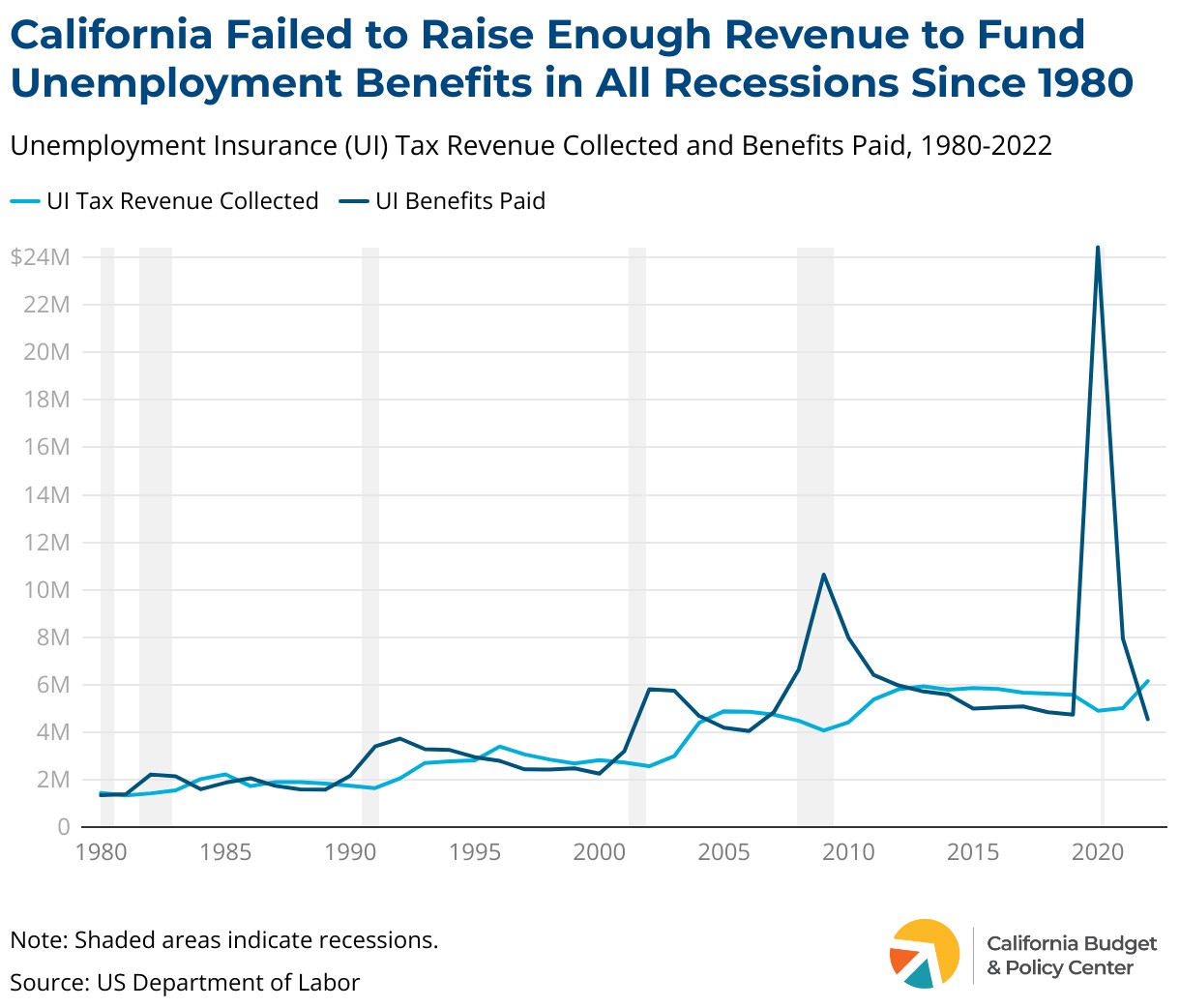

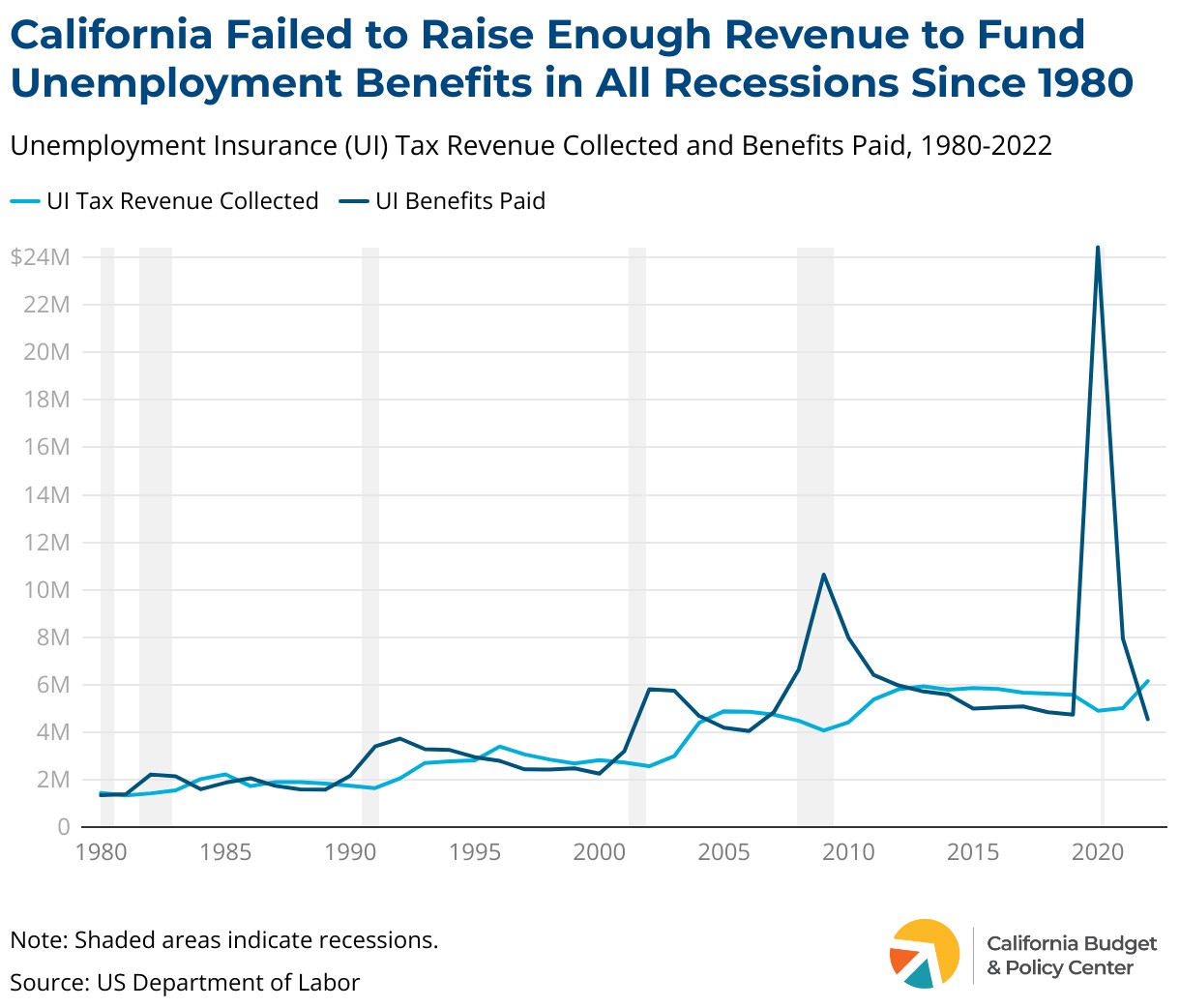

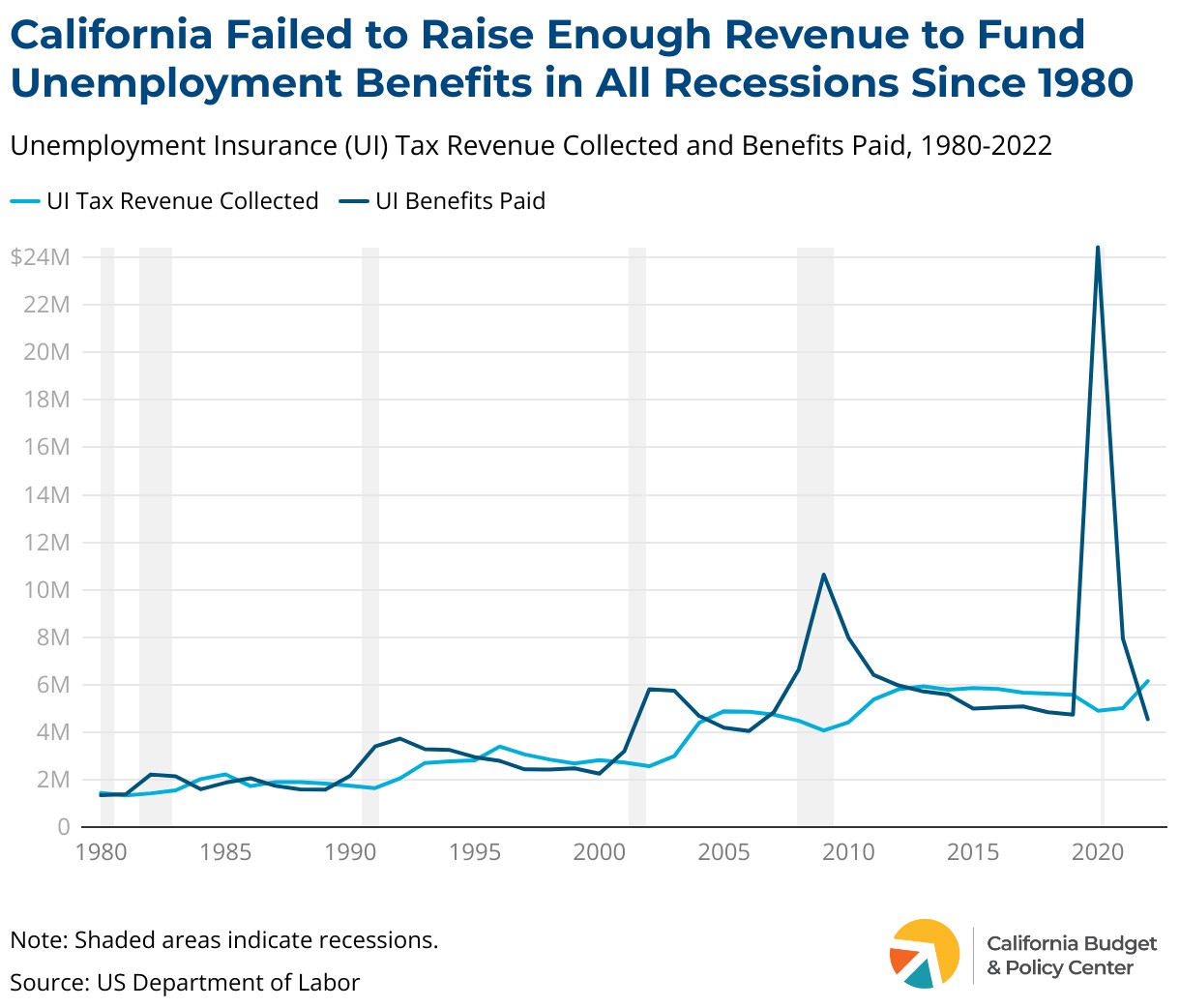

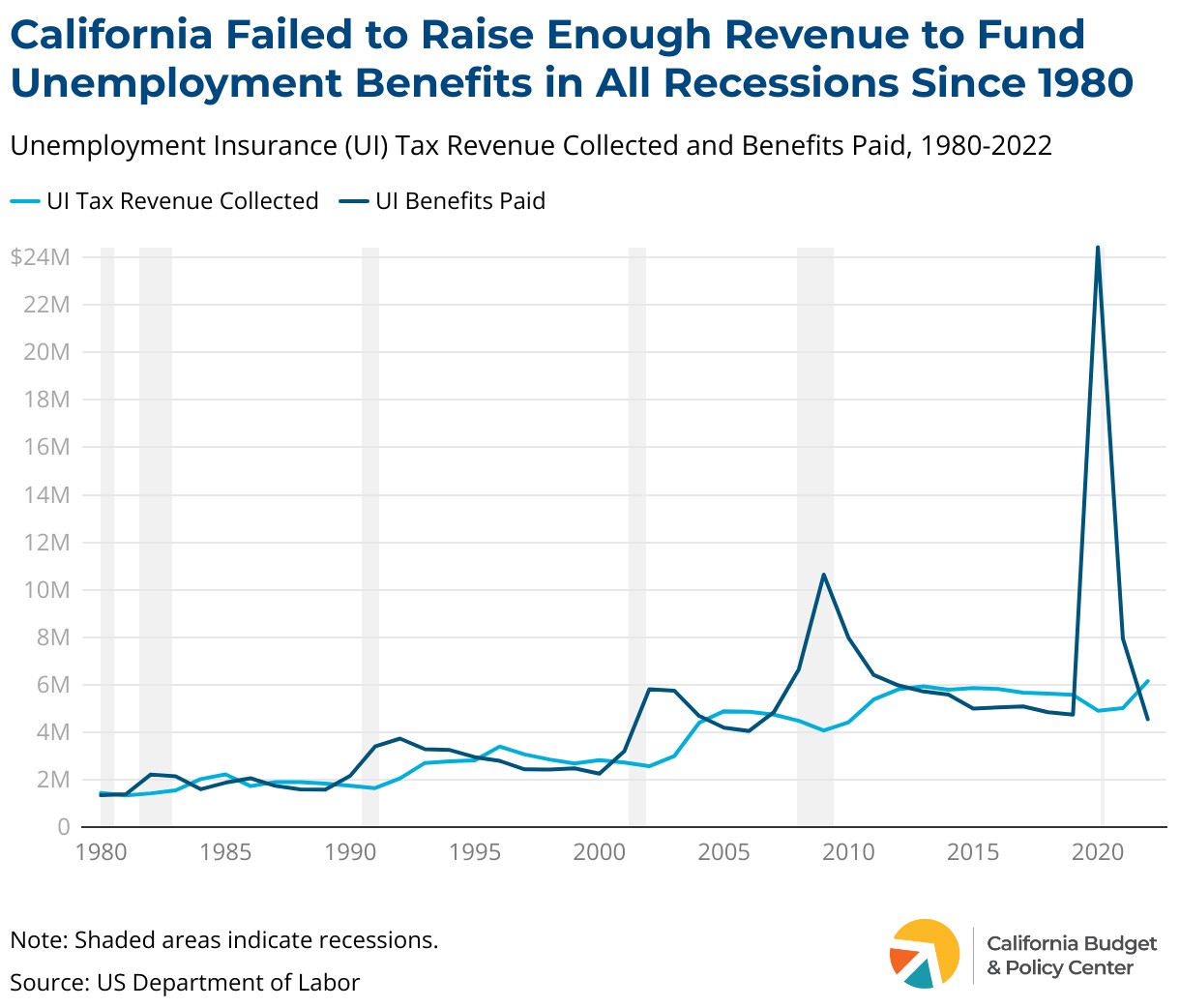

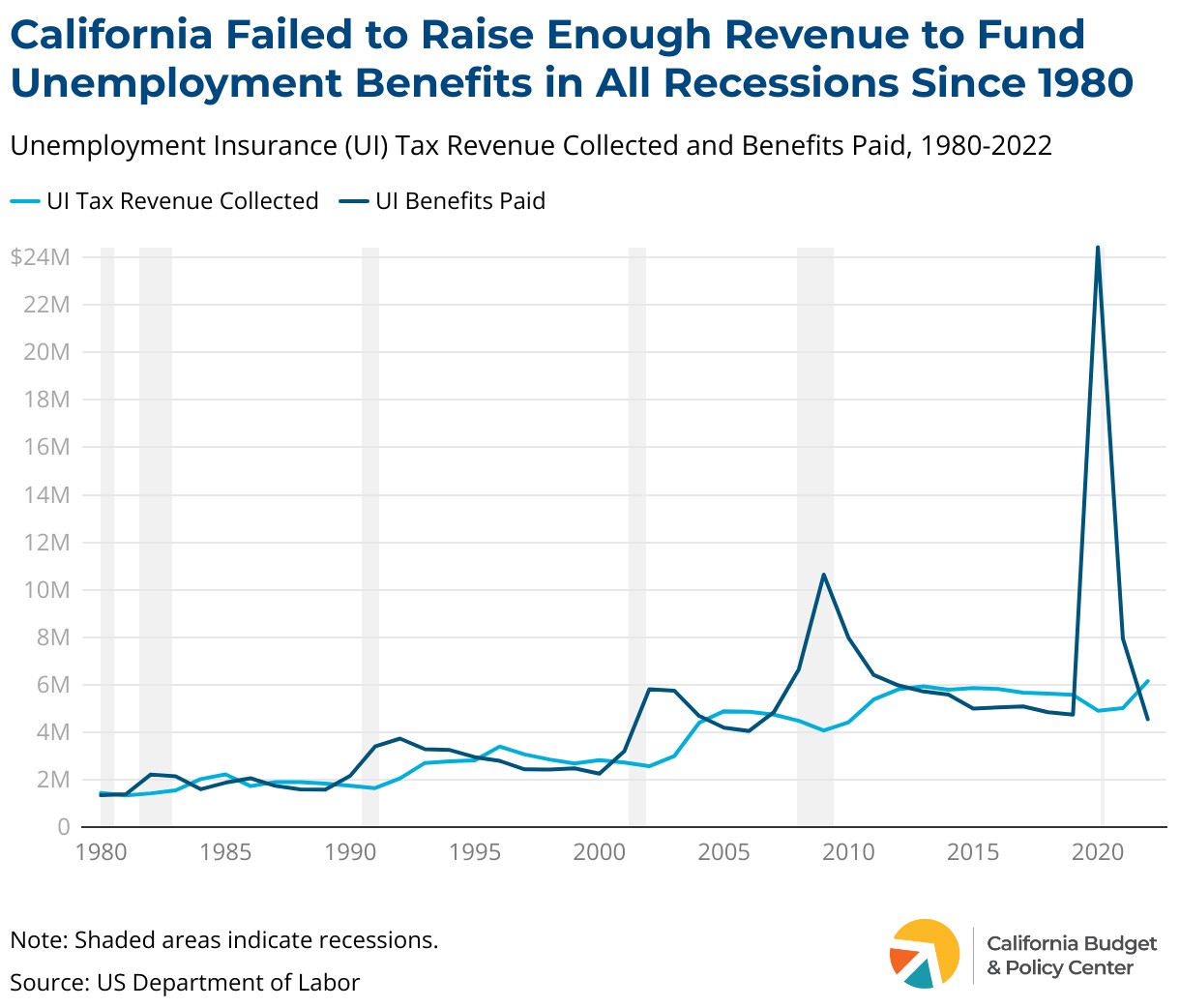

First, by hiking tax rates during economic downturns (when more workers are claiming UI benefits and the trust fund balance falls), the system compels businesses to pay higher taxes during the most difficult economic times, when their resources are most depleted. Raising business costs during recessions undermines UI’s ability to promote economic recovery. Second, by lowering tax rates as the trust fund balance begins to recover, this system makes raising additional revenue difficult. If California were to increase its taxable wage base without fixing the “pay-as-you-go” mechanism, employer tax rates would automatically fall as soon as the trust fund balance began to improve, making it more difficult to reach and maintain solvency. The weakness of pay-as-you-go financing is evident in California’s history: As the figure below indicates, the state failed to raise sufficient revenue to fund UI benefits in every recession since 1980.

11.1. The Benefits of Forward Financing

The alternative to California’s pay-as-you-go financing mechanism is a forward-funded system designed to take in more revenue than it pays out during periods of low unemployment. Forward funding enables state UI systems to build up sufficient reserves during economic growth to pay benefits during economic downturns, when large numbers of workers are laid off and seeking unemployment benefits. The US Department of Labor’s UI Trust Fund solvency standards are designed to encourage this type of forward funding. Numerous other states, including Oregon, use a forward-funding mechanism to put their UI systems on more stable financial footing.

11.2. Reforming Experience Rating

The mechanism for determining each individual employer’s UI tax rate is also flawed and needs to be reformed. In general, private employers are assigned a tax rate based on their experience with unemployment — that is, their history of laying off workers who then claim unemployment benefits. This system, known as “experience rating,” is required by the federal government, but states have considerable flexibility in selecting specific experience rating methods. In California, an employer’s experience rating is determined by a formula that takes into account their contributions into the trust fund and the UI benefits paid to their former workers.

There are two unintended consequences of this approach to experience rating. First, because employers’ contribution rate increases when their former employees claim UI benefits, employers have an incentive to discourage workers from applying for benefits, provide misinformation about eligibility, and dispute UI benefit claims. Second, this approach to experience rating makes raising the taxable wage base, on its own, a less effective strategy for improving UI financing. This is because increasing the taxable wage base would improve employers’ experience rating and automatically decrease their contribution rates (all else being equal), effectively limiting the amount of revenue that could be raised.

One potential alternative to this system is an experience rating system based on quarterly changes in the hours employees work for a given employer, regardless of whether these workers claim UI benefits. This would remove the incentive for employers to discourage or dispute benefit claims and would make increasing the taxable wage base more effective at shoring up the trust fund while supporting stronger benefits and broader eligibility.

Additionally, California could explore adopting this alternative experience rating system in combination with a method of assigning employer tax rates based on desired revenue targets, which researchers find is a highly effective strategy for improving UI financing. Finally, California should consider how app corporations like Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash, which use technology to set and control working conditions, short-change California’s UI system by misclassifying employees as independent contractors, circumventing traditional labor laws and taxes. A study from the UC Berkeley Labor Center finds that If Uber and Lyft had treated workers as employees, these two corporations alone would have paid $413 million into the state’s UI trust fund between 2014 and 2019.

12. Navigating Unemployment in California: Expert Guidance

Understanding the complexities of unemployment in California can be daunting. HOW.EDU.VN connects you with leading Ph.Ds and experts who provide personalized advice and solutions. Whether you’re grappling with job loss, seeking to understand your benefits, or aiming to improve your financial stability, our experts offer the guidance you need.

Here are five common scenarios where our expert consultations can be invaluable:

- Job Loss and Benefit Qualification: Understanding eligibility for unemployment benefits and navigating the application process.

- Financial Hardship: Strategies for managing financial challenges and accessing additional support during unemployment.

- Career Transition: Guidance on career changes, skill development, and job searching in a competitive market.

- Legal and Policy Insights: Understanding your rights and the latest policy changes affecting unemployment benefits.

- Mental Health Support: Accessing resources for mental health and well-being during periods of unemployment.

13. The Advantages of Consulting Ph.Ds at HOW.EDU.VN

HOW.EDU.VN provides a platform to connect directly with over 100 renowned Ph.Ds and specialists worldwide. Our professionals offer in-depth, customized consultations to address your unique needs.

13.1. Expertise and Experience

Our team comprises experts in various fields, including economics, labor law, career counseling, and financial planning.

13.2. Personalized Solutions

Receive tailored advice and strategies designed to meet your specific situation and goals.

13.3. Time and Cost Savings

Save time and money by accessing high-quality consultations without the traditional overhead costs.

13.4. Confidential and Reliable Information

Ensure the privacy and security of your information with trusted professionals.

13.5. Practical and Actionable Advice

Get advice and solutions that you can implement immediately to improve your circumstances.

Table: Featured Experts at HOW.EDU.VN

| Expert Name | Field of Expertise | Credentials |

|---|---|---|

| Dr. Anya Sharma | Economics | Ph.D. in Economics, University of California, Berkeley |

| Dr. Ben Carter | Labor Law | J.D., Ph.D. in Labor Studies, Harvard University |

| Dr. Chloe Davis | Career Counseling | Ph.D. in Counseling Psychology, Stanford University |

14. How to Connect with Our Experts

Connecting with our experts is simple and straightforward. Visit HOW.EDU.VN and follow these steps:

- Browse Our Experts: Explore our directory of Ph.Ds and specialists.

- Select Your Expert: Choose an expert whose background aligns with your needs.

- Schedule a Consultation: Book a convenient time for your consultation.

- Receive Personalized Advice: Get expert guidance and solutions tailored to your situation.

Address: 456 Expertise Plaza, Consult City, CA 90210, United States

WhatsApp: +1 (310) 555-1212

Website: HOW.EDU.VN

15. Call to Action: Secure Your Future Today

Don’t navigate the challenges of unemployment alone. Contact HOW.EDU.VN today and connect with our team of expert Ph.Ds to receive the personalized advice and support you need. Visit how.edu.vn or call us at +1 (310) 555-1212 to schedule your consultation.

FAQ: Understanding Unemployment in California

Q1: What is the current average unemployment benefit in California?

A: In 2023, the average unemployment benefit in California was $368.53 per week.

Q2: How does California’s unemployment benefit compare to other states?

A: California’s unemployment benefits are significantly lower than those in other Western states like Washington, Oregon, Nevada, and Hawaii.

Q3: Who is eligible for unemployment benefits in California?

A: Eligibility generally includes workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own and meet certain wage and work history requirements.

Q4: Are undocumented workers eligible for unemployment benefits in California?

A: No, undocumented workers are generally not eligible for regular unemployment benefits but may receive limited, one-time financial assistance through specific programs.

Q5: How is unemployment insurance funded in California?

A: Unemployment insurance is funded through state and federal payroll taxes paid by employers.

Q6: What is the taxable wage base in California?

A: California taxes employers on only the first $7,000 of each employee’s pay.

Q7: How does California’s taxable wage base compare to other states?

A: California has one of the lowest taxable wage bases in the country; 94% of US states have a higher taxable wage base.

Q8: What is experience rating, and how does it affect employer contributions?

A: Experience rating is a system where an employer’s tax rate is based on their history of laying off workers who then claim unemployment benefits. This can incentivize employers to discourage benefit claims.

Q9: What are the key issues with California’s current UI system?

A: Key issues include low benefit levels, exclusions of certain workers, a low taxable wage base, and a “pay-as-you-go” financing mechanism.

Q10: What reforms are needed to strengthen California’s UI system?

A: Reforms include raising the taxable wage base, shifting to a forward-financing mechanism, and reforming the experience rating system.