The pyramids of Egypt stand as colossal testaments to an ancient civilization, evoking awe and wonder across millennia. For generations, people have gazed upon these monumental structures, pondering not only their purpose and construction but also a fundamental question: How Old Are The Pyramids? While their imposing presence speaks volumes about the past, pinpointing their exact age requires delving into scientific methods, particularly radiocarbon dating, which has offered fascinating insights and complex challenges in our quest to understand the timeline of these iconic structures.

Radiocarbon Dating: A Scientific Clock for the Past

Radiocarbon dating is a method used by scientists to determine the age of organic materials by examining the decay of a radioactive isotope of carbon, known as Carbon-14 (C14). This isotope acts like a natural clock, as it decays at a known rate over time. Early pioneers in this field, like Willard F. Libby, recognized the potential of C14 dating for archaeology. In groundbreaking experiments, Libby’s team analyzed acacia wood from the Step Pyramid of Djoser, a 3rd Dynasty monument, to test their radiocarbon dating hypothesis. Their initial findings were remarkably consistent with their predictions based on C14’s half-life of 5568 years, suggesting the Djoser sample had approximately 50% of the C14 concentration found in living wood. This early success laid the foundation for further investigations into the age of ancient Egyptian artifacts and monuments. However, subsequent research revealed complexities, such as fluctuations in atmospheric C14 levels over time, necessitating the development of calibration techniques to refine the accuracy of radiocarbon dates.

Initial Radiocarbon Dating in 1984: Surprising Results

In 1984, a significant radiocarbon dating project was undertaken on materials from various Old Kingdom monuments in Egypt. This research, supported by the Edgar Cayce Foundation, aimed to compare radiocarbon dates with the historically accepted mid-point dates of the pharaohs associated with these monuments, as outlined in the Cambridge Ancient History. The results were intriguing but also raised questions. On average, the radiocarbon dates obtained were approximately 374 years older than the expected historical dates. Despite this considerable discrepancy, the 1984 radiocarbon dating project importantly confirmed that the Great Pyramid and other Old Kingdom monuments indeed belonged to the historical era that Egyptologists had already established through other means. This initial study underscored the potential of radiocarbon dating while also hinting at the complexities that would need further investigation.

The 1994-1995 Koch Foundation Project: A Broader Investigation

Driven by the initial findings and the desire for more comprehensive data, a second, more extensive radiocarbon dating project was launched in 1994-1995, supported by the David H. Koch Foundation. This project broadened the scope of sampling to include materials from a wider range of sites and monuments, spanning several dynasties:

- 1st Dynasty tombs at Saqqara (2920-2770 BC)

- The Djoser pyramid (2630-2611 BC)

- The Giza Pyramids (2551-2472 BC)

- 5th Dynasty pyramids (2465-2323 BC)

- 6th Dynasty pyramids (2323-2150 BC)

- Middle Kingdom pyramids (2040-1640 BC)

The 1994-1995 project also included samples from the Giza Plateau Mapping Project’s Lost City excavations. Notably, the excavation of two well-preserved bakeries in the Lost City in 1991 yielded valuable samples of ash and charcoal, materials highly suitable for radiocarbon dating. The results from this second round of dating presented a nuanced picture. The 1995 dates generally tended to be 100 to 200 years older than the Cambridge Ancient History dates, but interestingly, they were also about 200 years younger than the dates obtained in the 1984 study.

Comparing 1984 and 1995 Data: Discrepancies and Variations

The combined datasets from the 1984 and 1995 projects allowed for statistical comparisons, particularly for the pyramids of Djoser, Khufu (Great Pyramid), Khafre, and Menkaure. Two significant observations emerged from this comparative analysis. First, there were notable discrepancies between the 1984 and 1995 radiocarbon dates for the pyramids of Khufu and Khafre, but not for Djoser and Menkaure. Second, the 1995 dates exhibited considerable variation even within samples taken from a single monument. For example, dates from Khufu’s Great Pyramid spanned a range of approximately 400 years.

Areas of Agreement: Middle Kingdom and 1st Dynasty Dates

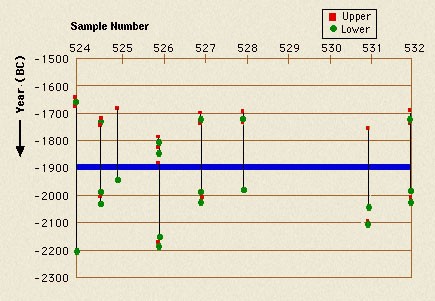

Despite the variations and discrepancies in Old Kingdom dating, there were areas of agreement that provided valuable context. For the 1st Dynasty tombs at North Saqqara, the radiocarbon dates from the 1995 project aligned reasonably well with both historical dates and previously obtained radiocarbon dates on reed material. Similarly, for the Middle Kingdom, there was a fair degree of agreement between radiocarbon dates and historical dates. Eight calibrated dates from straw samples taken from the pyramid of Senwosret II (1897-1878 BC) showed a range from 103 years older to 78 years younger than the historical dates for his reign. Remarkably, four of these dates were remarkably close, differing by only 30, 24, 14, and three years. It is worth noting that the oldest date in this set came from a charcoal sample, hinting at a potential issue known as the “old-wood problem.”

Radiocarbon dating test results from the Middle Kingdom pyramid of Senwosret II, illustrating the range and variation in dates obtained from different samples.

The “Old-Wood Problem”: A Challenge to Accurate Dating

A significant factor complicating the accurate radiocarbon dating of ancient Egyptian sites, particularly the pyramids, is the “old-wood problem.” Ancient Egypt, constrained by the Nile Valley’s narrow geography, likely had limited tree cover. By the pyramid age, it is probable that the Egyptians had already been extensively exploiting wood resources for fuel and various purposes for a considerable period. Given the scarcity and value of wood, recycling and reuse were common practices. Pieces of older wood might have been reused multiple times, even burned as fuel in activities like mortar preparation. If wood that was already centuries old was burned to create charcoal for mortar, radiocarbon dating of that charcoal would yield dates centuries older than the actual construction of the mortar itself. While researchers initially considered it unlikely that pyramid builders consistently used centuries-old wood for mortar preparation, the 1984 results, with dates significantly older than expected, prompted a re-evaluation of this possibility and led to the more extensive 1995 study. The question arose: were the radiocarbon estimations fundamentally in error, or was the historical chronology of the Old Kingdom significantly off?

Reusing Ancient Materials: Another Layer of Complexity

Beyond the “old-wood problem,” another factor potentially influencing radiocarbon dating results is the ancient Egyptians’ practice of reusing older cultural materials. Pyramid builders might have reused older materials for expediency or perhaps to intentionally create a symbolic link between a pharaoh and his predecessors. Evidence of this practice has been found at various sites. For example, beneath the 3rd Dynasty pyramid of Djoser, archaeologists discovered over 40,000 stone vessels. These vessels bore inscriptions of kings from the earlier 1st and 2nd Dynasties, while Djoser’s name appeared only once, suggesting that Djoser might have collected and reused vases already 200 years old from tombs at North Saqqara. Further compelling evidence comes from the 12th Dynasty, where Amenemhet I (1991-1962 BC) demonstrably recycled materials. He incorporated pieces of Old Kingdom tomb chapels and pyramid temples, including those from the Giza Pyramids, into the core of his own pyramid at Lisht. This practice of material reuse further complicates the interpretation of radiocarbon dates, as samples could potentially reflect the age of the reused material rather than the construction date of the pyramid itself.

Radiocarbon dating test results from the 5th Dynasty pyramid of Sahure, illustrating the range and variation in dates, possibly influenced by material reuse.

Radiocarbon dating from the Lost City excavations near the Giza pyramids also provided intriguing insights. Three out of eight radiocarbon dates from the Lost City were remarkably close to Menkaure’s historical reign dates (2532-2504 BC). However, the remaining five dates were significantly older, ranging from 100 to 350 years earlier. This scatter of dates from the Lost City, similar to that observed in pyramid samples, suggests that inhabitants of the Lost City, who were likely involved in pyramid construction over approximately 85 years, were also recycling settlement debris, contributing to the older radiocarbon dates.

Conclusions: What Radiocarbon Dating Tells Us About Pyramid Age

In conclusion, radiocarbon dating of materials from the Egyptian pyramids has provided valuable but complex insights into their age. The “old-wood problem” and the practice of reusing older materials are significant factors contributing to the scatter and often older-than-expected radiocarbon dates obtained from Old Kingdom monuments. While these challenges make pinpointing the exact construction dates of the pyramids solely through radiocarbon dating difficult, the research has yielded broader and more nuanced understandings.

The radiocarbon dating projects, particularly the extensive 1994-1995 study, have moved researchers to consider wider implications. The wide scatter of dates and the “history-unfriendly” results from the Old Kingdom pyramids may reflect a significant environmental impact of early pyramid construction – potentially indicating a major depletion of Egypt’s exploitable wood resources during the early Old Kingdom. The immense scale of pyramid construction in this period might have driven the pyramid builders to exploit any available wood, possibly even resorting to scavenging for fuel to produce the vast quantities of gypsum mortar, forge copper tools, and bake bread for the massive workforce.

Therefore, while definitively answering “how old are the pyramids?” with precise calendar years remains an ongoing challenge, radiocarbon dating has profoundly enriched our understanding. It has shifted the focus from simply seeking exact dates to exploring broader questions about ancient Egyptian forest ecologies, site formation processes, ancient industry, and the environmental and societal impact of constructing these monumental landmarks. The Egyptian pyramids, as hallmarks of ancient human civilization, continue to inspire research that delves into the intricate society and economy that brought them into existence.