I. Decoding Tumor Antigens: An Essential Guide

The breakthroughs in anti-tumor immunotherapy and advancements in next-generation sequencing for mutation profiling have significantly improved our understanding of the specific targets of anti-tumor T cells. Mutated proteins are emerging as promising targets for autologous T cell therapies and engineered cell therapies. They also serve as crucial indicators of the effectiveness of immunoregulatory interventions, including immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). Tumors, being mutated self-tissues, present a unique challenge to the host’s immune system, which is primarily designed to combat foreign pathogens. This resemblance to self can hinder immune recognition, yet the fundamental aspects of anti-tumor responses appear to mirror those against pathogens. Identifying effective antigenic targets and therapeutically elicitable responses are central questions in this field. This article delves into current knowledge regarding anti-tumor specificity, immunogenic mutations, and how cross-reactivity and immunodominance contribute to the variability of immune responses across different tumor types.

II. Types of Tumor Antigens: A Detailed Classification

Both CD8 and CD4 αβ T cells recognize peptides (p) in the context of class I and class II major histocompatibility complexes (MHC), respectively. Viral immunology has been instrumental in defining pMHC epitopes from various pathogens, establishing fundamental principles applicable across infectious models. These principles include:

- Central Tolerance: Self-epitopes are distinguished from pathogenic epitopes through central tolerance. T cell receptors with strong reactivity to self-epitopes are eliminated in the thymus via negative selection. However, self-reactive T cells can still emerge in the periphery.

- Limited Epitope Sampling: Despite the vast potential of the T cell repertoire, only a small fraction of the viral proteome is processed to generate targets for host immunity.

- Consistent Immune Response Profiles: Individuals sharing the same MHC tend to exhibit similar response magnitudes to identical epitopes from the same pathogens. These predictable immune response patterns, known as immunodominance hierarchies, are influenced by factors such as peptide presentation in MHC, pMHC complex stability, and the characteristics of the T cell receptor repertoire.

Central tolerance restricts the immune system’s access to certain features of the tumor proteome. The specificity of the immune response in cancer is crucial from both immunological and tumor perspectives. Immunological specificity, shaped by evolution to combat foreign pathogens, enables the immune system to distinguish self from non-self with high precision. However, cancer presents an evolutionary paradox. While tolerance mechanisms prevent autoimmune reactions against self-antigens, they can also limit the diversity, repertoire, and function of tumor-reactive immune cells. This has driven the search for an ideal cancer target: an antigenic target abundant in cancer cells but absent in normal tissues. The following sections and Table 1 outline three major categories of tumor antigens—tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), cancer-germline/cancer testis antigens (CTAs), and tumor-specific antigens (TSAs)—discussing their specificity and prevalence across patients and cancer types.

Table 1. Tumor Antigen Types: Advantages and Disadvantages for Therapy

This table summarizes the spectrum of tumor antigens, ranging from low to high tumor specificity, providing examples and evaluating their therapeutic potential.

| Class of tumor antigen | Description of antigen | Examples of antigen type | Advantages of targeting | Disadvantages of targeting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigens with low specificity | Differentiation antigen | Proteins with cell lineage-specific expression or present during specific developmental stages. | CD19, MART-1, gp100, TRP2, CEA | – Shared antigenic targets across patients – Potential for off-the-shelf treatments |

| Overexpressed antigen | Normal cellular proteins with increased expression in cancerous cells. | WT1, ERBB2, PRAME, RAGE-1, mesothelin | – Shared antigenic targets across patients – Potential for off-the-shelf treatments | – Difficulty in quantifying relative abundance on tumor versus normal cells – Risk of on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

| Antigens with high specificity | Mutated antigens | Gene mutations resulting in novel peptide expression (point mutations, frameshift mutations, chromosomal translocations). | CDK4, KRAS, BRCA1/2, p53, TGF-βRII | – Reduced likelihood of on-target, off-tumor toxicity – Potential sharing of driver/fusion mutations in same cancer types |

| Oncogenic viral antigen | Abnormal proteins from oncovirus-infected cells, causing various cancers. | HPV E6/E7, EBV EBNA1/LMP1/LMP2 | – Viral antigens shared among patients with virus-related cancers – Potential for off-the-shelf treatments | – Relatively low prevalence of cancers with known viral origins |

| Cancer/testis (germline) antigens | Expressed in testes, fetal ovaries, or trophoblasts, absent in healthy somatic cells. Selectively expressed in specific cancers. | MAGE, BAGE, GAGE, NY-ESO-1 | – Shared antigenic targets in patients with same cancer type – Potential for off-the-shelf treatments | – Not universally expressed across all cancer types – Potential for unexpected on-target, off-tumor toxicity |

III. Low Tumor Specificity Antigens: Tumor Associated Antigens (TAAs)

Tumor Associated Antigens: Understanding TAAs

Tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) are among the most extensively studied and earliest targets in cancer vaccine development. TAAs are normal host proteins exhibiting differential expression between host and tumor cells. Dysregulation of gene pathways due to tumor cell mutations often leads to abnormal expression of unmutated proteins. These proteins are typically expressed at lower levels or not at all in normal cells of the same tissue type at the same developmental stage. TAAs encompass differentiation antigens, shared between tumors and normal tissues of origin but distinct from other tissues, and overexpressed antigens, aberrantly expressed normal proteins that promote tumor growth and/or survival.

Differentiation Antigens: Targeting Lineage-Specific Proteins

Differentiation antigens have garnered significant interest as potential targets for immunotherapy, largely due to melanoma research. Studies have documented spontaneous T cell responses against peptides derived from GP100(1–4), Melan-A/MART-1(5, 6), and tyrosinase(7, 8). While these responses were observed in melanoma due to antigen expression patterns on melanoma cells, the potential to treat a broader patient population continues to fuel research into targeting cancerous cells that abnormally express differentiation antigens. CD19, a differentiation antigen found on normal and malignant B cells, is another example. It is targeted in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and other B cell tumors (reviewed in(9)). Adoptive transfer of anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells has achieved high complete remission rates (up to 90%) in relapsed and refractory ALL patients, highlighting the potency of this immunotherapy(9). However, anti-CD19 therapies may also affect non-cancerous cells due to CD19 expression across B cell development, potentially leading to off-target antigenicity. Consequences can range from temporary loss of non-essential cells to permanent damage of vital tissues, requiring further treatment. Ideal differentiation antigens are derived from proteins normally expressed only during early development.

Overexpressed Antigens: Targeting Abundant Proteins in Tumors

Overexpressed antigens, another TAA class, are implicated in driving malignancy in various tumors. Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) is commonly overexpressed in leukemia cells, contributing to oncogenesis(10, 11). In epithelial tumors like breast and ovarian cancer, ERBB2 (HER2/NEU) overexpression is linked to poor prognosis but can be an immunotherapy target due to increased expression on highly proliferative cancerous cells(12, 13).

The appeal of targeting TAAs lies in their shared expression across patients and cancer types, enabling broadly applicable, off-the-shelf treatments. However, their similarity to self-peptides limits endogenous T cell responses due to central tolerance or lower T cell receptor p/MHC binding affinity compared to foreign antigens(14). Recent studies caution against adoptive transfer or receptor engineering approaches against TAAs, citing on-target, off-tumor toxicities. For instance, a metastatic colon cancer patient treated with ERBB2-targeted CAR T cells died from off-tumor effects on lung epithelial cells expressing low ERBB2 levels(15).

IV. High Tumor Specificity Antigens: CTAs and TSAs

Cancer/Testis Antigens: Exploring CTAs

Van der Bruggen and colleagues identified MAGE-1, the first human tumor antigen, a cancer/testis antigen (CTA) recognized by endogenous T cells(16). CTAs are expressed in testes, fetal ovaries, or trophoblasts but are absent in healthy somatic cells. Since the early 1990s, the focus on specificity has increased the interest in CTAs. Their attractiveness is attributed to: 1) disrupted gene regulation in tumors, 2) limited normal tissue expression, 3) absence in germline and trophoblastic cells (which lack MHC class I molecules), and 4) immunogenic potential. While CTA-targeted vaccines and adoptive cell therapies (ACT) show promise in clinical trials with NY-ESO-1(17) and MAGE(18), a MAGE-A3-targeted ACT trial led to severe toxicities and death due to unexpected gene expression in the brain(18).

Tumor-Specific Antigens: Unveiling TSAs

Tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) typically arise from tumor-specific mutations, resulting in neoantigen expression exclusively in tumors and absent in normal cells. Viral proteins from oncovirus infections like HPV(19, 20) and EBV(21) are also sources of TSAs eliciting tumor recognition. TSAs’ cancer-restricted expression theoretically leverages the immune system’s ability to differentiate self from non-self, bypassing tolerance mechanisms that eliminate high-affinity self pMHC-binding tumor-reactive T cells. Studies in 2005 supported neoantigens’ dissimilarity to self, making them targetable(22, 23). Robbins et al. demonstrated complete tumor regression in a melanoma patient after adoptive transfer of ex vivo-expanded tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) recognizing mutated GAS7 and GAPDH(23). Wolfel et al. showed that autologous T cells exhibited stronger responses against neoantigens than TAAs in human melanoma using cDNA library screens(22). These early findings, along with advancements in next-generation sequencing and epitope prediction algorithms, have shifted focus towards personalized immunotherapies targeting TSAs.

Efforts to utilize TSAs therapeutically and characterize responses in ICB therapy patients have led to detailed mapping of TSA-specific T cells. Melanoma studies consistently reveal that only a small fraction of potential neoepitopes induce detectable T cell responses(24). “Hit rates” for finding tetramer-positive or peptide-reactive T cells can be as low as 0.5–2% of screened antigens. For example, in one study, a melanoma patient with 249 non-synonymous mutations, 126 predicted to bind HLA-A*0201, showed T cell responses to only 2 of 126 neoantigens screened against TILs. However, healthy donor PBMCs in vitro cultures showed responses to a larger proportion of these peptides(25). Another melanoma study detected only one T cell response from 75 tetramers corresponding to potential tumor epitopes(26).

Several factors explain the low response rate to potential neoepitopes. Predicted neoepitopes may not be processed and presented on tumors. Some studies validate predicted peptide binding to HLA molecules experimentally(27). A CLL patient study confirmed HLA binding for 18 candidate neoepitope peptides, yet only one elicited a detectable response. Beyond neoepitope overestimation, nonresponsiveness may result from repertoire constraints due to self-similarity, though this likely has a limited impact. The low response rate raises concerns about low mutation burden tumors, common in pediatric cancers, which may not generate sufficient TSAs and TAAs for effective endogenous T cell targeting.

V. Mutational Landscape and Neoantigen Generation

Tumor neoantigen generation is a consequence of genomic instability in cancer cells. Accumulated mutations and genomic rearrangements disrupt gene pathways, preventing cell death, limiting division, or causing further instability, interfering with genes crucial for these processes(28). Somatic mutations and rearrangements leading to mutated or chimeric amino acid chains are particularly relevant to tumor antigenicity. These can be drivers of cancer or tumor-specific “hitchhikers,” with the latter potentially more susceptible to immune escape.

Mutation load varies significantly across cancers, from 0.8 to over 47 coding mutations per megabase (median), with some exceeding 1,200 per megabase(29). Mutation load relates to patient age(29) and cancer/tissue type, with skin and lung cancers typically having the most mutations and leukemias the fewest(29–31). Novel peptides from tumor mutations correlate with total mutation burden. Studies on neoepitope immune responses focus on highly mutated cancers, where, on average, fewer than 2% of investigated mutations elicit endogenous T cell responses(25, 26, 32). Cancer neoantigens are often considered a probabilistic process, where more mutations increase the likelihood of immunogenic neoantigen generation. This discourages broad immunotherapy application, as many adult and most pediatric tumors have low somatic mutation rates. A recent study identified HLA alleles predicted to present tumor driver mutations poorly, finding that tumors with these drivers and HLA haplotypes were rare(33. When such tumors occurred, they often showed allelic loss of the relevant HLA gene(34. Endogenous T cell responses to tumor-specific neoepitopes offer targeted antigens for patient-specific vaccination and receptors for T cell engineering therapeutics.

While vaccination and T cell receptor engineering require direct TSA identification, immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) is not constrained similarly. ICB therapies (targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1) enhance T cell activity against cancer neoantigens, showing remarkable clinical activity against diverse tumors(35–37. Although ICB doesn’t target specific antigens, melanoma(38, 39) and non-small-cell lung carcinoma(40–42) trial data suggest that mutation load and neoantigen abundance correlate positively with objective response rates to ICB(43). This confirms immune system recognition and targeting of neoantigens in highly mutated cancers but doesn’t preclude responses in lower mutation burden tumors. Munson et al.(44) found that CD8 T cell infiltration and TCR sharing in breast cancer correlated with improved survival. Shared TCRs were detected between breast cancer patients’ TILs and blood but rarely in cancer-free controls, suggesting tumor-specificity. While viral or environmental antigen recognition wasn’t ruled out, tumor-involved lymph node T cells were four times more likely to contain shared TCRs compared to tumor-free lymph node T cells. Further TCR reconstruction studies are needed to confirm tumor antigen specificity, but these findings reinvigorate efforts to identify and prioritize therapeutic treatments exploiting the immune system to target tumor antigens across cancers.

VI. Immunodominance in Cancer: Shaping Immune Responses

Cancer arises from accumulated genetic alterations, leading to mutant protein (neoantigen) production absent in host cells(28, 30). Theoretically, the upper limit of neoantigens is approximated by somatic mutations and rearrangements. However, viral models sHow This overestimates expressed and presented antigens, as MHC class I antigen presentation pathways reduce potential antigenic peptides(45). Peptide processing narrows the pool of presented peptides, but peptide-MHC binding affinities are crucial. Insufficient affinity results in unstable pMHC complexes, limiting peptide expression on the cell surface. Abelin et al.(46) used a mono-allelic cell expression system and mass spectrometry to profile the HLA peptidome, considering expression and peptide-MHC binding. This approach accurately reflects peptides presented by single HLA allele-transduced B cells, but generalizability to primary tumor cells with multiple HLA alleles requires further study. For immune response induction, T cells need cognate TCRs with sufficient pMHC avidity, resulting in polyclonal CD8+ T cells recognizing immunodominant and subdominant antigens. This phenomenon, immunodominance(45), limits the breadth of targets. Immunodominance is a structured response hierarchy among epitope-specific T cell populations targeting subsets of antigens. Studied in pathogen infections, it shows small epitope subsets generating cognate T cell responses with reliable magnitude hierarchies. Infections with the same pathogen in MHC-identical animals typically produce similar response profiles.

Immunodominance mechanisms are not fully understood. Proposed factors include pMHC complex number on the cell surface, responding T cell precursor frequency, peptide-MHC binding affinity and off-rate, and pMHC:TCR interaction avidity(47–49). However, some associations, like precursor frequency, were not consistently observed in models like influenza(50).

Immunodominance may focus anti-tumor responses on a small subset of neoepitopes or TAA-derived epitopes. Hepatocellular carcinoma TAA response studies show immunodominance across patients, with each patient targeting a small subset of expressed TAAs, but no consistent preferential antigen targeting across patients(51). Factors like protein expression variation, processing efficiency, and HLA polymorphisms influence epitope presentation. Response breadth correlated with improved progression-free survival, analogous to HCV, where CD8 T cell response breadth correlates with viral control(52). Strong hierarchy is also seen in melanoma patient responses to NY-ESO-1 TAA(53). While these show CD8 T cell anti-tumor response immunodominance, underlying mechanisms are unclear. Further studies are needed to determine if tumor antigen expression levels, response induction speed, or other factors shape the repertoire.

Immunodominance’s potential to regulate anti-tumor responses is recognized, impacting immunotherapy and cancer vaccination(54, 55). Immunodominance variation in individuals with different HLA haplotypes contributed to NY-ESO-1 vaccination outcome differences(56). Identifying immunodominant response predictors could improve tumor antigen computational pipelines (Figure 1). If low response rates to TSA and TAA landscapes are partly due to immunodominant focusing, even low mutation burden tumors may elicit useful responses. A larger proportion of available neoepitopes might be targeted in these tumors, as TSA- and TAA-driven response limitation may stem from immunodominant focusing, not antigenicity lack. Future low mutation burden tumor response studies should address this hypothesis(57).

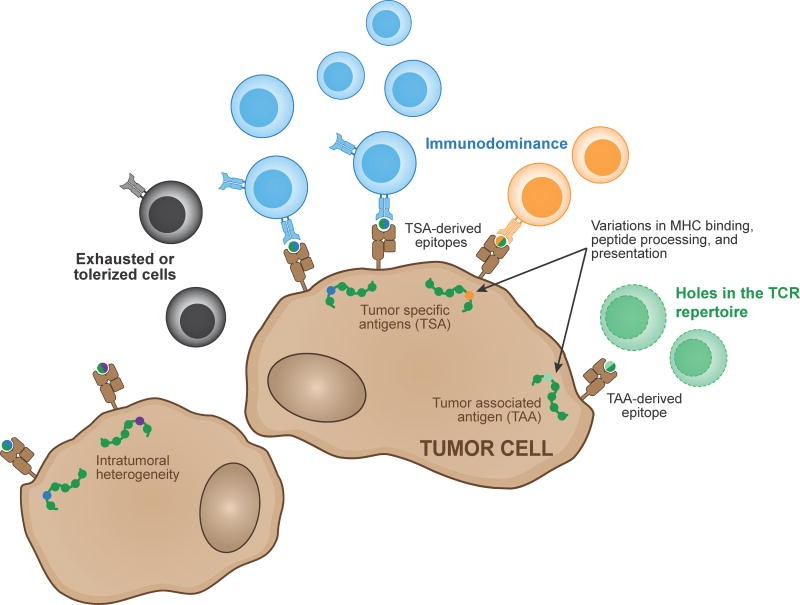

Figure 1. Determinants of Anti-Tumor T Cell Reactivity

Two main antigen types, tumor-associated and tumor-specific, are recognized by endogenous T cell responses. Epitope detection by T cells is influenced by host HLA type and epitope processing and presentation efficiency. Intratumoral heterogeneity can enable tumor cell escape. Immunodominance hierarchies can result in a major antigen target. TCR repertoire gaps and T cell tolerization and exhaustion can limit response effectiveness.

VII. Specificity and Cross-Reactivity: Navigating the Immune Landscape

TSAs are promising targets for tumor clearance while minimizing normal tissue effects. TSA-focused strategies involve eliciting or generating T cell pools against defined TSAs via vaccination or TCR transduction. TSAs are often highly similar to self, with single mutations underlying most characterized TSAs. Exceptions include insertions, deletions, or fusions, creating epitopes differing from parent self-peptides by multiple amino acids.

TSA-derived epitopes and self’s close relationship raise concerns about repertoire limitations and cross-reactivity. Negative selection should underrepresent or eliminate self-reactive TCRs. While TSAs differ from self, their proximity may limit the responding repertoire if TSA-reactive TCRs also react to parent self-epitopes. However, recent studies suggest negative selection’s repertoire restrictions may be limited. Human T cell response studies found peripheral T cells against self-antigens like SMCY in males, albeit at lower levels than in females and in a tolerogenic state, but reactivatable with higher antigen doses(58). Mutating a single residue in an epitope without disrupting peptide-MHC binding generated epitopes reliably binding T cells. This suggests few absolute repertoire holes, with clonal deletion “pruning” self-reactive specificities. Thus, even epitopes proximal to self can be recognized by T cells.

TSA-derived epitopes from single nucleotide variants are analogous to viral infection epitope mutations facilitating immune escape. These mutations can limit or evade immune repertoires against original epitopes, as seen in HIV and HCV persistence(59). Similarly, TSAs may not share reactive immune repertoires with T cells targeting unmutated self-peptides. Neoepitope prediction pipelines incorporate distance-to-self in TSA immunogenicity prediction(60, 61). Two factors are considered: 1) mutation creating a peptide processing cleavage site, and 2) sufficient biochemical distinction for TCRs unlikely to cross-react with self. The latter is hard to model due to limited prediction of peptide:MHC:TCR interactions, but divergent amino acid residues are more likely to create distinct epitope surfaces.

Vaccination studies using TSA targets in melanoma further demonstrate repertoire ability to mount anti-TSA responses. Healthy HLA-matched donors elicited responses against melanoma patient tumor antigens(25). Many were private mutations, and healthy donors showed robust responses to these mutated epitopes, though elicitation methods differed from patient PBMCs. Recent studies successfully immunized melanoma patients with TSA arrays and adjuvant, boosting autologous responses in patients previously exposed to these antigens(62, 63).

While repertoire limitations can be overcome, TSA-targeted approaches may induce cross-reactive responses to parent self-epitopes, breaking tolerance, especially for adoptive TCR transfer therapies. Analogous to CAR TCR therapies, TSA-epitope-specific TCRs are engineered into autologous T cells, expanded, and infused. However, TCRs cross-reacting with self-epitopes could lead to targeting of unmutated parent self-epitopes. Beyond off-target affinity for parent epitopes, unexpected reactivities can occur, as in a MAGE-A3-targeted TCR therapy trial where the TCR also targeted a self-epitope from muscle protein Titin(64). This TCR, derived from an endogenous response but affinity-enhanced, did not respond to the Titin-derived epitope at wild-type concentrations, suggesting endogenous peripheral tolerance shapes anti-tumor responses away from significant self-reactivity.

Engineered TCR self-reactivity limitation strategies are suggested. Endogenous TCRs may limit self-reactivity due to central and peripheral tolerance. In vitro selected or humanized mouse model TCRs may have undetected reactivities and be antigenic themselves (65). Promiscuous pairing of introduced TCR chains with endogenous chains can create hybrid receptors with varied targets(66). Altering TCR constant regions to favor cognate engineered chain pairing, via second cysteine introduction or murine homologue swapping, enhances TCR expression on the cell surface (67, 68).

Introduced TCR off-target or undetected specificity raises cross-reactivity concerns. TCR repertoire cross-reactivity is estimated to be vast (over one million peptides per TCR in one report(69)). TCR repertoire cross-reactivity is inferred from adaptive immunity principles: broad immune reactivity to novel antigens, vast MHC-binding peptide landscape, and TCR repertoire size. Potential pMHC target pool size is orders of magnitude greater than individual repertoire size. While TCRs are cross-reactive, cross-reactivity “neighborhoods” are less clear(70).

A landmark study identified individual TCR targets via yeast display libraries, showing TCRs target conserved peptide surface features but are agnostic to changes at other peptide residues(71). Despite diverse peptide targets, consistent commonalities allowed prediction of unobserved reactive peptides. Even dissimilar reactive peptides could be “connected” by single-mutation-away reactive peptide series.

Predictive aspects suggest determining if a TCR reacts with both TSA-derived epitopes and parent peptides, although current in silico approaches lack sufficient training data for this.

VIII. Conclusion: Future Directions in Tumor Antigen Targeted Therapies

T cell-mediated tumor therapies fall into three categories: 1) adoptive cell therapies, 2) vaccines, and 3) immune modulating therapies like ICB and cytokine therapy. Specificity characterization is vital for the first two. ICB can be used without TSA or TAA knowledge, but studies link tumor mutation burden (especially neoepitope burden) to improved outcomes(29, 40, 72). This association may correlate with overall anti-tumor response magnitude, or high-quality responses may be more likely with more TSAs available.

For therapies in development, shared targets across individuals are attractive for off-the-shelf therapies. CD19 CAR T cells, NY-ESO-1 vaccines, and adoptive TCR therapies targeting common fusions and driver mutations are broadly applicable across tumor types. However, focusing on single targets (or multiple epitopes from one target) may increase tumor escape. Targeting multiple mutations is more likely to prevent escape and address heterogeneous mutation landscapes. Finding multiple targets in a tumor often requires private antigenic targets (patient-specific mutations), increasing therapeutic development complexity, but their promise justifies workflow development.

Isolating and cloning tumor-specific TCRs is now relatively rapid. Specificity determination remains a bottleneck but may not always be necessary. Algorithms predicting TCR specificity are advancing, improving TCR sequence-epitope matching efficiency(73, 74). Cloning and expressing TCRs enables engineering cells for increased function, reduced exhaustion, and safety features like kill switches or multiple antigen specificity requirements(75, 76. These features offer the best hope for safe and effective therapies, despite remaining technological challenges, by generating high tumor specificity and reducing off-target effects.

IX. Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA021765, R01AI107625, and ALSAC.

X. References

[1] van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991 Oct 18;254(5032):1643-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. PMID: 1840703.

[2] Bakker AB, Schreurs MW, de Boer AJ, Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA, Adema GJ, Figdor CG, Boon T, Scheeren FA. Melanocyte lineage-specific antigen gp100 is recognized by melanoma-derived tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994 Nov 1;180(5):1623-31. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1623. PMID: 7964455; PMCID: PMC2191726.

[3] Cox AL, Skipper J, Chen Y, Henderson RA, Darrow TL, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH, Slingluff CL Jr, Engelhard VH, et al. Identification of a peptide recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. Science. 1994 Apr 8;264(5156):716-9. doi: 10.1126/science.8160258. PMID: 8160258.

[4] Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Sakaguchi K, Robbins PF, Rivoltini L, Yannelli JR, Appella E, Austin FC, Dodd TH, Greenstein JL, et al. Identification of a human melanoma antigen recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Nov 22;91(22):10581-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10581. PMID: 7972065; PMCID: PMC45041.

[5] Coulie PG, Brichard VG, Van Pel A, Wolfel T, Schneider J, Traversari C, Mattei S, De Plaen E, Lurquin C, Szikora JP, et al. Cytolytic T-lymphocyte epitopes on MAGE-1 human melanoma antigen. Int J Cancer. 1991 Dec 20;48(6):873-9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480612. PMID: 1659883.

[6] Kawakami Y, van den Eynde B, Elíyahu S, Sakaguchi K, Fetters P, Robbins PF, Dupont B, Warnke R, Beachy PA, Boon T, et al. Recognition of multiple epitopes of a melanoma antigen, MART-1, by tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1994 Aug 1;153(3):1158-66. PMID: 8036767.

[7] Wolfel T, Van Pel A, Brichard V, Schneider J, Seliger B, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Boon T. Two tyrosinase nonapeptides recognized on HLA-A2 melanomas by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1994 Oct;24(10):2593-8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241036. PMID: 7925428.

[8] Castelli C, Storkus WJ, Maeurer MJ, Martin Seco E, Hwang WL, Peterson JT, Kast WM, Parmiani G, Lotze MT. Mass spectrometric identification of a naturally processed melanoma peptide recognized by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1995 Mar 1;181(3):1163-8. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1163. PMID: 7864227; PMCID: PMC2191933.

[9] Sadelain M, Rivière I, Brentjens R. Targeting CD19 with autologous T cells modified to express chimeric antigen receptors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2012;354:153-70. doi: 10.1007/82_2011_194. PMID: 22127645; PMCID: PMC3309549.

[10] Call KM, Glaser T, Ito CY, Buckler AJ, Pelletier J, Haber DA, Rose EA, Kral A, Yeger H, Lewis WH, et al. Isolation and characterization of a zinc finger polypeptide gene at the human chromosome 11 Wilms’ tumor locus. Cell. 1990 Jul 27;60(3):509-20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90704-E. PMID: 2105529.

[11] Gessler M, Poustka A, Cavenee W, Neve RL, Orkin SH, Bruns GA. Homozygous deletion in Wilms tumour-derived cell lines of a region mapped to chromosome band 11p13. Nature. 1990 Jan 18;343(6255):272-5. doi: 10.1038/343272a0. PMID: 2153541.

[12] Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, Bassett WW. Human breast and ovarian cancer cells overexpress a new c-erbB-2 gene product. Science. 1987 Mar 6;235(4785):177-82. doi: 10.1126/science.3798598. PMID: 3798598.

[13] Hynes NE, Stern DF. The biology of erbB-2/neu/HER-2 and its role in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994 Aug 15;1198(2-3):165-84. doi: 10.1016/0304-419X(94)90074-0. PMID: 8077814.

[14] Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:51-88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.51. PMID: 10358753.

[15] Morgan RA, Yang JC, Kitano M, Dudley ME, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol Ther. 2010 Feb;18(4):843-51. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.24. Epub 2010 Feb 9. PMID: 20145631; PMCID: PMC2841849.

[16] van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991 Oct 18;254(5032):1643-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. PMID: 1840703.

[17] Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Jul 9;99(10):7030-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102139799. Epub 2002 May 14. PMID: 12011453; PMCID: PMC122985.

[18] Morgan RA, Chinnasamy N, Abate-Daga D, Rosati SF, Duran E, Romero Z, Zack PM, Maus MV, Warren SE, Yang JC, et al. Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy. J Immunother. 2013 Sep;36(9):133-51. doi: 10.1097/CJ.0b013e3182a323c1. PMID: 23982527; PMCID: PMC3929148.

[19] Tindle RW, Crawford DH, Finlayson CJ, McMillan NA, Gulrajani R, Kreider JW, Jarrett RF, Parkinson JE, LYons TJ, Smith SK, et al. Human papillomavirus-16-associated high-grade cervical neoplasia in transgenic mice. J Gen Virol. 1990 Jul;71 ( Pt 7):1343-53. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-7-1343. PMID: 2165190.

[20] Feltkamp MC, Smits HL, Vierboom MP, Vermeij P, van den Putten H, Stormink H, Fuijen RH, Kast WM, Melief CJ, Jan JT. Vaccination with cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-containing peptide protects against a tumor induced by human papillomavirus type 16 E6/E7 transforming proteins. Eur J Immunol. 1993 Oct;23(10):2242-9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231004. PMID: 8223853.

[21] Khanna R, Burrows SR, Argaet VP, Coupar BE, Saunders NA, Fazou C, Moss DJ. Endogenous cytotoxic T cell response to Epstein-Barr virus antigens in nuclear antigen-negative Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer Res. 1992 Oct 15;52(20):5847-51. PMID: 1394149.

[22] Wolfel T, Hauer M, Schneider J, Serrano M, Wolfel C, Klehmann-Hieb E, De Plaen E, Hankeln T, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Knuth A, et al. A p16INK4a-insensitive CDK4 mutant targeted by cytolytic T lymphocytes in a human melanoma. Science. 1995 Oct 27;269(5232):1861-4. doi: 10.1126/science.269.5232.1861. PMID: 7569905.

[23] Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Nahvi AV, Marincola FM, Leitman SF, et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma after transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes selected in vitro for reactivity to melanoma-self antigens. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Aug 15;22(15):3038-47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.157. PMID: 15284248.

[24] Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015 Apr 3;348(6230):69-74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4976. PMID: 25838375; PMCID: PMC4758199.

[25] Linnemann C, van Buuren MM, Honselaar A, Kessler JH, Verdegaal EM, Bouwen RD, Bakker AB, Schotte R, Van den Broek M, van de Watering MJ, et al. High-throughput epitope discovery using genome-wide libraries of synthetic peptides. Nat Biotechnol. 2015 May;33(5):534-44. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3191. Epub 2015 Apr 6. PMID: 25844866.

[26] Cafri G, Gartner JJ, Zaks T, Hopkins J, Miller JJ, Luo Y, Seth A, Abate R, Marincola FM, Stroncek DF, et al. Immunoediting and clonal evolution in the course of melanoma metastasis is shaped by immune pressure. JCI Insight. 2017 Feb 9;2(3):e90803. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90803. PMID: 28179987; PMCID: PMC5327441.

[27] Fritsch EF, Rajasagi V, Ott PA, Brusic V, Hacohen N, Wu CJ. Neoantigen personalized cancer vaccines come of age. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014 May;2(5):405-11. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0035. PMID: 24831578; PMCID: PMC4015485.

[28] Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011 Mar 4;144(5):646-74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. PMID: 21376230.

[29] Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, McKenna A, Lander ES, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013 Feb 14;494(7436):495-501. doi: 10.1038/nature11879. PMID: 23434461; PMCID: PMC3598829.

[30] Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013 Mar 29;339(6127):1546-58. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. PMID: 23539594; PMCID: PMC3749880.

[31] Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013 Aug 22;500(7463):415-21. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. PMID: 23917296; PMCID: PMC3773052.

[32] Castle JC, Sahin U. Immunotherapy targeting cancer mutanomes. Genome Med. 2016 Jul 12;8(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0325-z. PMID: 27401539; PMCID: PMC4942041.

[33] McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R, Ramskov S, Lyngaa R, McGrail L, Rowan AJ, Howarth LM, Watkins AJ, Dogan A, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 2016 Apr 1;351(6280):1463-9. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1498. PMID: 26997492; PMCID: PMC5001395.

[34] Riaz N, Havel JJ, Makarov V, Desrichard A, Urba WJ, Rizvi NA, Sharma P, Allison JP, Chan TA. Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy with nivolumab. Cell. 2017 Feb 9;168(3):449-464.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.028. PMID: 28157491; PMCID: PMC5300730.

[35] Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):711-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. PMID: 20526032; PMCID: PMC3549296.

[36] Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Hamid O, Kefford R, Weber JS, Joshua AM, Hohl M, Gangadhar TC, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2014 Sep 20;384(9948):1109-17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60958-2. Epub 2014 Jun 10. PMID: 24928207; PMCID: PMC4329019.

[37] Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Bartlett CH, Segal NH, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jun 28;366(26):2443-54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. PMID: 22658127; PMCID: PMC3544589.

[38] Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, Walsh LA, Cummings A, Chan TA, Hodi FS, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 11;371(23):2189-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. PMID: 25422465; PMCID: PMC4357272.

[39] Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Rizvi NA, Weber JS, Ribas A, Chapman PB, Lo RS, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015 Oct 9;350(6257):207-11. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0080. PMID: 26453491; PMCID: PMC4832454.

[40] Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Hoang P, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015 Apr 3;348(6230):124-8. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. PMID: 25765070; PMCID: PMC4468435.

[41] Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Lee MK, Lu C, Ngo VN, Valsangkar B, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 25;372(26):2509-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500564. PMID: 26028255; PMCID: PMC4481136.

[42] Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L, et al. Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 21;372(21):2018-28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. Epub 2015 Apr 19. PMID: 25951379.

[43] Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015 Apr 3;348(6230):69-74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4976. PMID: 25838375; PMCID: PMC4758199.

[44] Munson JM, Dodson LF, Pinheiro EM, Rakheja D, Chappell R, Teague JE, Forde MM, Olson BM, Box KM, Peterson CB, et al. High-avidity T cell clones specific for shared tumor antigens are selected in vivo and mediate antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 2018 Apr;8(4):449-463. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0915. Epub 2018 Feb 8. PMID: 29419469; PMCID: PMC5883129.

[45] Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:51-88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.51. PMID: 10358753.

[46] Abelin JG, Keskin DB, Sarkizova S, Hartigan BM, Zhang W, Sidney J, Stevenson BJ, Verdegaal EM, Bethune MT, Chihrin S, et al. Mass spectrometry profiling of HLA-associated peptides reveals widespread presentation of neo-antigens in human cancers. Immunity. 2017 Feb 21;46(2):315-326. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.007. PMID: 28219528; PMCID: PMC5334937.

[47] Bousso P, Levraud JP, Kourilsky P. Immunodominance of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses: a potential mechanism. Eur J Immunol. 1998 Jul;28(7):2048-56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199807)28:073.0.CO;2-W. PMID: 9686823.

[48] Jenkins MR, Griffith JP, Davey GM, Jackson DC, Brooks AG. Peptide-MHC class I complex stability is a critical determinant of T cell activation threshold. J Immunol. 2002 Apr 15;168(8):3747-56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3747. PMID: 11937560.

[49] Kersh EN, Allen PM. Essential flexibility in the T-cell receptor-major histocompatibility complex class II interaction. Nature. 1996 Nov 28;384(6607):336-9. doi: 10.1038/384336a0. PMID: 8945466.

[50] Welsh RM, McNally JM, Brehm MA, Selin LK. Virus-induced inflammatory প্রাইমিং and immunodominance. Immunol Rev. 2001 Dec;184:79-93. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2001.18407.x. PMID: 11882273.

[51] Wada Y, Nakatsura T, Seike M, Satoh S, Yamada T, Nishimura Y, Yoshimura K, Gleissner CA, Smith DD, Hoffmann TK, et al. Identification of immunodominant tumor-associated antigens as potential targets for cancer vaccine development. J Immunother. 2004 Sep-Oct;27(5):372-80. doi: 10.1097/00004782-200409000-00007. PMID: 15353896.

[52] Wedemeyer H, Tillmann HL, Manns MP. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19(1):21-40. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007106. PMID: 10195558.

[53] Zarling AL, Savage PA, Weber J, Rosasco MG, Wolchok JD, Allison JP. NY-ESO-1-specific T cell clones vary in their TCR usage, avidity and capacity for self-recognition. Int Immunol. 2000 Nov;12(11):1577-86. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1577. PMID: 11053292.

[54] Melief CJ, van der Burg SH. Immunotherapeutic vaccines targeting tumor-associated antigens. Immunol Rev. 2008 Apr;222:107-22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00614.x. PMID: 18397225.

[55] Finn OJ. Cancer immunology. Immunity to cancer: why can’t we translate mouse models to humans? Immunity. 2008 Feb;28(2):149-57. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.01.004. PMID: 18267098.

[56] Lee PP, Yee C, Savage PA, Fong EC, Brockstedt D, Weber JS, Johnson D, Swetter S, Thompson JA, Greenberg PD, et al. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat Med. 1999 Jun;5(6):677-85. doi: 10.1038/9534. PMID: 10370313.

[57] Gubin MM, Zhang X, Schuster H, Caron E, Ward JP, Noguchi T, Ivanova Y, Hundal J, Arthur CD, Krebber WJ, et al. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature. 2014 Nov 13;515(7528):577-81. doi: 10.1038/nature13988. PMID: 25411763; PMCID: PMC4480331.

[58] Дербикян С., Зарецкий Ю. Ю., Андреева А. В., Козлов В. А., Швец И. М. Роль пептид-МНС-комплексов в формировании иммунного ответа на опухолевые антигены. Иммунология. 2018;39(6):325–334. [Derbickyan S, Zaretsky YuYu, Andreeva AV, Kozlov VA, Shvets IM. Role of peptide-MHC complexes in the formation of immune response to tumor antigens. Immunologiya. 2018;39(6):325–334. (In Russ.)].

[59] Goulder PJ, Watkins DI, Matthews PC. HIV and SIV CTL escape: implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009 Oct;9(10):713-25. doi: 10.1038/nri2623. PMID: 19779466; PMCID: PMC2794833.

[60] Luksza M, Riaz N, Makarov V, Balachandran VP, Hellmann MD, Solovyov A, Rizvi NA, Merghoub T, Levine AJ, Chan TA, et al. Neoantigen burden as a predictor of clinical benefit from PD-1 blockade in melanoma, lung and bladder cancers. Ann Oncol. 2017 Mar 1;28(3):474-480. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw567. PMID: 27980043; PMCID: PMC5834196.

[61] Offringa R, van den Burg SH, Ossendorp F, Toes RE, Melief CJ. Design and evaluation of antigen-based cancer vaccines. Semin Immunol. 2000 Apr;12(2):87-95. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0228. PMID: 10788315.

[62] Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB, Shukla SA, Kim PS, Ji Z, Chen CJ, McDermott DF, Radvanyi LG, Wrangle JM, et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature. 2017 Jul 6;547(7662):217-221. doi: 10.1038/nature22991. PMID: 28678777; PMCID: PMC5676992.

[63] Sahin U, Derhovanessian E, Miller M, Kloke BP, Simon P, Lower M, Bukur V, Tadmor AD, Luxemburger U, Schrörs B, et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature. 2017 Jul 6;547(7662):222-226. doi: 10.1038/nature23003. PMID: 28678778.

[64] Willemsen R, Debets R, Ossendorp F, Melief CJ. Cancer immunotherapy: T-cell receptor gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2003 Aug;10(15):1261-8. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302099. PMID: 12879068.

[65] Bendle GM, Linnemann C, Hooijberg E, Wiemer EA, van Buuren MM, Haanen JB, Schumacher TN. Universal TCRs for cancer gene therapy. Nat Med. 2010 Oct;16(10):565-72. doi: 10.1038/nm.2215. Epub 2010 Sep 19. PMID: 20852622.

[66] Stauss HJ, Thomas S, Weber JM. The role of hybrid T-cell receptors in autoimmune disease and anti-tumour immunity. Immunology. 2011 Jul;133(3):265-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03460.x. PMID: 21535221; PMCID: PMC3121323.

[67] Bethune MT, Prinzing BL, Hsiung SJ, Weiss R, Krouse AB, Alarid ET, Wittrup KD. Preferential pairing of heterodimeric TCRαβ constant domains facilitates T cell receptor gene therapy. J Immunol. 2016 Feb 1;196(3):1218-25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502097. Epub 2015 Dec 23. PMID: 26703877; PMCID: PMC4728468.

[68] Bulman CA, Tucci J, March L, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI, Baxter AG. Preferential pairing of transgenic TCR chains is sufficient to promote T cell development and function in the absence of endogenous TCRα recombination. J Immunol. 2010 Sep 1;185(5):2899-909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001179. Epub 2010 Jul 28. PMID: 20660770.

[69] Mason D. A very high level of crossreactivity is an essential feature of the T-cell receptor. Immunol Today. 1998 Nov;19(11):395-404. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01335-3. PMID: 9817109.

[70] Glanville J, Huang H, Nau A, Hatton O, Wagar LE, Loeb PA, Lerner RA, Sundar PD, Heath JR, পড়ন্ততয়। I ট্র্যাভেলস। Relating T-cell receptor sequence to antigen specificity. Nature. 2017 Jan 12;541(7637):382-385. doi: 10.1038/nature29953. Epub 2016 Dec 21. PMID: 28002428; PMCID: PMC5549161.

[71] Dash P, Mora T, Weinberger AD, Callan CG Jr, Wuchty S, Bialek W. Deep learning for immunological sequence analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2017 Jul;35(7):276-279. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3830. Epub 2017 Apr 17. PMID: 28414991; PMCID: PMC5527388.

[72] Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Song C, Moreno BH, Hu-Lieskovan S, Beroukhim R, Bolen JB, Gogas H, Dahlman KB, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic characterization of primary and acquired resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell. 2016 Mar 24;165(1):35-44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.067. PMID: 27015368; PMCID: PMC4802264.

[73] Glanville J, Huang H, Nau A, Hatton O, Wagar LE, Loeb PA, Lerner RA, Sundar PD, Heath JR, পড়ন্ততয়। I ট্র্যাভেলস। Relating T-cell receptor sequence to antigen specificity. Nature. 2017 Jan 12;541(7637):382-385. doi: 10.1038/nature29953. Epub 2016 Dec 21. PMID: 28002428; PMCID: PMC5549161.

[74] Dash P, Mora T, Weinberger AD, Callan CG Jr, Wuchty S, Bialek W. Deep learning for immunological sequence analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2017 Jul;35(7):276-279. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3830. Epub 2017 Apr 17. PMID: 28414991; PMCID: PMC5527388.

[75] June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 15;378(1):60-71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706169. PMID: 29345388.

[76] Fedorov VD, Themeli M, Sadelain M. PD-1- and CTLA-4-based inhibitory chimeric antigen receptors (iCARs) divert off-target immunotherapy responses. Sci Transl Med. 2013 Dec 4;5(215):215ra172. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007001. PMID: 24310154; PMCID: PMC4005415.