Understanding formal charge is a fundamental concept in chemistry, essential for predicting molecular structures, reaction mechanisms, and resonance forms. While it might seem daunting at first, calculating formal charge is a straightforward process once you grasp the basic principles. This guide will break down the process into easy-to-follow steps, providing clear examples and addressing common challenges encountered by students. Whether you’re just starting your chemistry journey or need a refresher, this comprehensive explanation will equip you with the skills to confidently calculate formal charge for any atom in a molecule.

1. What is Formal Charge? Understanding the Basics

Formal charge is a concept used in chemistry to assign a charge to an atom in a molecule, assuming that electrons in all chemical bonds are shared equally between atoms, regardless of relative electronegativity. It’s a bookkeeping method, helping us predict the most plausible Lewis structures and understand electron distribution within molecules. It’s important to note that formal charge is not the actual charge of an atom in a molecule but rather a theoretical charge based on an idealized model of bonding.

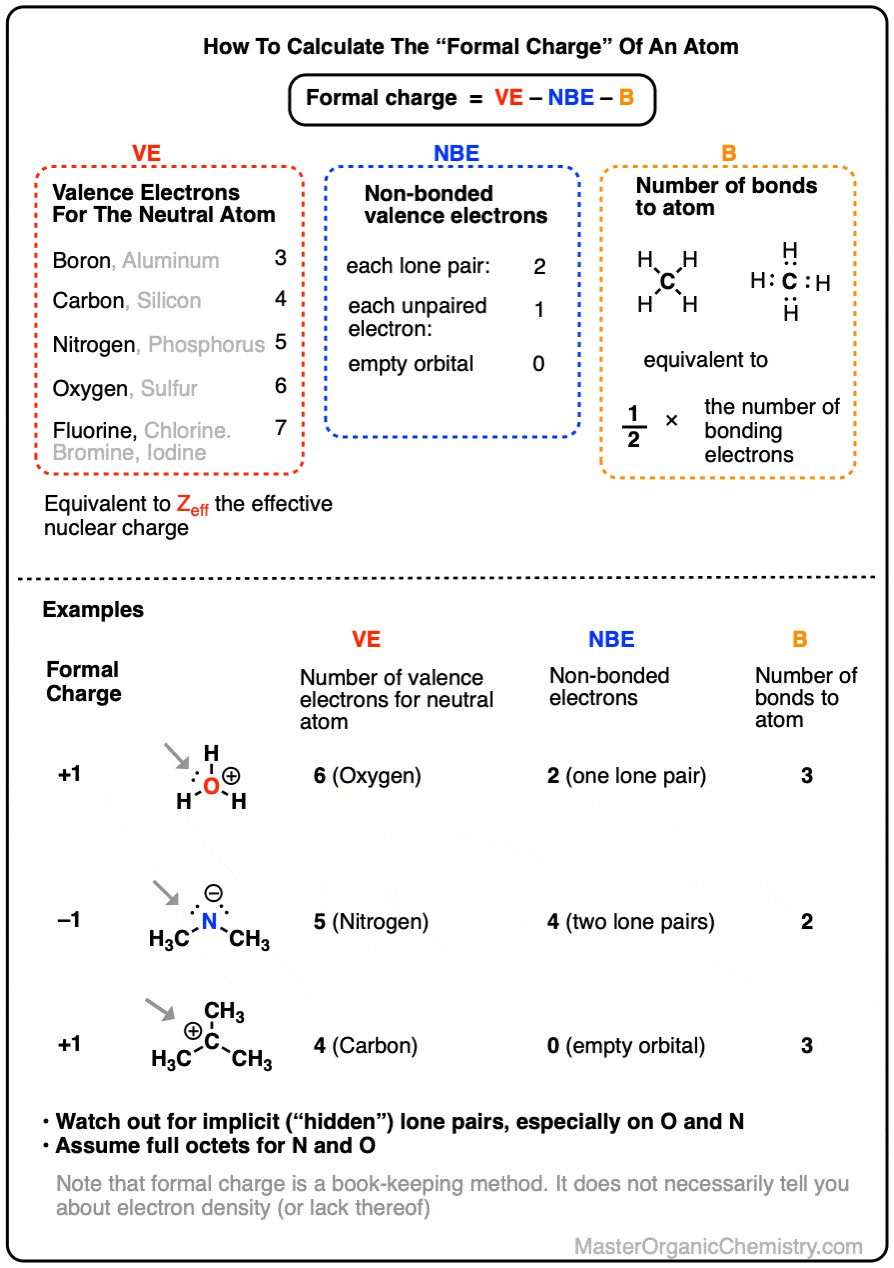

To calculate formal charge, we use a simple formula that takes into account the valence electrons of a neutral atom, the number of non-bonding electrons it possesses in the molecule, and the number of bonds it forms.

The formula for formal charge (FC) is:

FC = VE – (NBE + B)

Alternatively, this can be written as:

FC = VE – NBE – B

Where:

- VE = Number of Valence Electrons in the neutral atom. This is the number of electrons in the outermost shell of an isolated atom. You can easily find this from the atom’s group number on the periodic table (e.g., Group 14 (or IVA) elements like Carbon have 4 valence electrons, Group 15 (or VA) elements like Nitrogen have 5, and so on). This is related to the effective nuclear charge, representing the positive charge “seen” by valence electrons.

- NBE = Number of Non-Bonding Electrons. These are valence electrons that are not involved in bonding and are also known as lone pair electrons. Each lone pair counts as 2 non-bonding electrons, and a single unpaired electron counts as 1.

- B = Number of Bonds. This is the number of covalent bonds an atom forms in the molecule. Each bond represents a shared pair of electrons. You can also think of this as half the number of bonding electrons.

It’s crucial to understand that formal charge is a “formalism.” It operates under the assumption of perfect covalent bonding, where electrons are shared equally. It does not account for differences in electronegativity between atoms, which in reality, leads to unequal sharing of electrons and partial charges (dipoles). Therefore, while formal charge is a valuable tool, it’s not always a direct indicator of actual charge distribution or reactivity within a molecule. We will explore the implications of this later in this guide.

2. Step-by-Step Calculation with Simple Examples

Let’s walk through some straightforward examples to illustrate How To Calculate Formal Charge, focusing on elements commonly encountered in organic chemistry, such as first-row elements.

Consider the hydronium ion, H₃O⁺. We want to find the formal charge on the central oxygen atom.

- Identify the central atom: In H₃O⁺, it’s oxygen (O).

- Determine Valence Electrons (VE): Oxygen is in Group 16 (or VIA), so a neutral oxygen atom has 6 valence electrons. (VE = 6)

- Count Non-Bonding Electrons (NBE): In H₃O⁺, the oxygen atom has one lone pair of electrons. Therefore, NBE = 2.

- Count Bonds (B): The oxygen atom is bonded to three hydrogen atoms, so it forms 3 bonds. (B = 3)

- Apply the Formula:

FC = VE – (NBE + B) = 6 – (2 + 3) = 6 – 5 = +1

Thus, the formal charge on the oxygen atom in the hydronium ion (H₃O⁺) is +1. This is why the hydronium ion carries a positive charge.

Let’s take another example, the hydroxide ion, OH⁻, and calculate the formal charge on oxygen.

- Central Atom: Oxygen (O)

- Valence Electrons (VE): For oxygen, VE = 6.

- Non-Bonding Electrons (NBE): In OH⁻, the oxygen atom has three lone pairs of electrons. So, NBE = 6.

- Bonds (B): The oxygen atom is bonded to one hydrogen atom, forming 1 bond. (B = 1)

- Apply the Formula:

FC = VE – (NBE + B) = 6 – (6 + 1) = 6 – 7 = -1

The formal charge on the oxygen atom in the hydroxide ion (OH⁻) is -1, which corresponds to the overall negative charge of the hydroxide ion.

Now, test your understanding with these examples. Calculate the formal charges for all atoms in the following molecules:

- Ammonia (NH₃) – Calculate for Nitrogen

- Methane (CH₄) – Calculate for Carbon

- Boron trifluoride (BF₃) – Calculate for Boron

You can use the following interactive quiz to check your answers and reinforce your understanding:

Click to Flip

Practice is key! The more you work through examples, the more intuitive calculating formal charge will become. Soon, you’ll be able to recognize common bonding patterns and quickly determine formal charges without needing to write out the formula every time.

Here’s a table for further practice. Try to fill in the formal charges for each atom in these examples:

To solidify your knowledge, consider exploring interactive quizzes and exercises online. Many resources offer immediate feedback to help you learn effectively. With consistent practice, formal charge calculations will become second nature.

3. Dealing with Implicit Lone Pairs and Bonds in Skeletal Structures

Often in organic chemistry, particularly when using skeletal or line-angle formulas, not all lone pairs and atoms (especially hydrogens bonded to carbon) are explicitly drawn. This can initially complicate formal charge calculation. However, understanding these conventions is crucial for working with chemical structures efficiently.

Think of it like this: when you see a simplified drawing of a molecule, you’re expected to “fill in” the missing details based on your understanding of valency and the octet rule (or duet rule for hydrogen).

Carbon:

- In skeletal structures, carbon atoms are typically represented by the vertices and ends of lines.

- Hydrogen atoms bonded to carbon are often omitted. You need to infer their presence to ensure each carbon atom has an octet (or is electron deficient in cases like carbocations).

- If a carbon atom has a formal charge, or lone pairs, or unpaired electrons, these are always explicitly drawn.

Oxygen and Nitrogen (and Halogens):

- Bonds to hydrogen are usually shown for oxygen, nitrogen, and halogens.

- Lone pairs on oxygen, nitrogen, and halogens are frequently omitted, but you are expected to assume they are present to complete the octet around these atoms.

- Oxygen and nitrogen almost always achieve a full octet. (There are rare exceptions, especially in reactive intermediates, but for most common structures, assume an octet).

Let’s illustrate with examples. Consider a nitrogen atom in a molecule where only one bond is explicitly drawn, and no lone pairs are shown. To calculate the formal charge, you must first infer the missing lone pairs.

Nitrogen, being in Group 15, has 5 valence electrons. To achieve an octet and form only one bond, it needs to have three lone pairs (6 non-bonding electrons).

So, for this nitrogen:

- VE = 5

- NBE = 6 (from three lone pairs)

- B = 1

FC = 5 – (6 + 1) = -2

Therefore, this nitrogen atom would have a formal charge of -2.

Here are more examples to practice inferring implicit details and then calculating formal charge:

Click to Flip

Remember the analogy of a stick figure: omitting fingers doesn’t mean they’re missing unless explicitly drawn that way! Similarly, in chemistry, omissions are conventions, not indicators of missing components essential for formal charge calculation.

Now, try these examples, combining implicit hydrogens and lone pairs:

Click to Flip

Putting it all together, practice with these more complex examples:

Click to Flip

(Note: Some of these examples might represent reactive intermediates or resonance forms, not necessarily stable molecules. The principles of formal charge calculation still apply.)

4. Advanced Formal Charge Problems: Exotic Molecules

The formal charge formula remains consistent, even when dealing with complex or unfamiliar-looking molecules. Don’t be intimidated by complex structures! The same step-by-step approach will guide you to the correct formal charges. The key is to systematically count valence electrons, non-bonding electrons, and bonds for each atom.

Let’s tackle some classic, slightly more challenging formal charge problems:

Click to Flip

Even for reactive intermediates like radicals and carbenes, the formal charge calculation process is identical. Just carefully count electrons and bonds.

Click to Flip

The beauty of formal charge is its universality. Regardless of molecular complexity, the fundamental formula and principles apply. Practice with diverse examples to build confidence and speed in your calculations.

5. Formal Charge and Curved Arrows in Mechanisms

Formal charge plays a crucial role in understanding and representing reaction mechanisms using curved arrows. Curved arrows illustrate the movement of electron pairs during chemical reactions and resonance. (See post: Curved Arrows For Reactions).

Changes in formal charge are directly linked to the movement of electrons depicted by curved arrows. Let’s consider the reaction of hydroxide ion (HO⁻) with a proton (H⁺).

The curved arrow originates from the lone pair on oxygen in HO⁻ and points towards the proton (H⁺). This arrow signifies the movement of two electrons from oxygen to form a new O-H bond.

Notice how formal charge changes: At the arrow’s tail (oxygen), the formal charge becomes more positive (from -1 to 0). At the arrow’s head (H⁺), the formal charge becomes more negative (from +1 to 0).

In the reaction of acid with water to form hydronium ion (H₃O⁺), we can use curved arrows to represent the protonation of water.

Try this quiz: Draw the curved arrow showing the formation of hydronium ion (H₃O⁺) from hydroxide ion and water.

Click to Flip

A common mistake is to draw the arrow towards the positively formally charged oxygen in H₃O⁺. Why is this incorrect?

Oxygen, even with a positive formal charge, still obeys the octet rule. It does not have an empty orbital to accept another pair of electrons. Drawing an arrow to the oxygen would imply forming an O-O bond and violating the octet rule by giving oxygen ten electrons.

This highlights a crucial point: formal charge is not electrostatic charge. While oxygen in H₃O⁺ has a +1 formal charge, the actual positive charge in the hydronium ion is distributed across the hydrogen atoms due to the polar O-H bonds. Oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, pulling electron density towards itself.

Therefore, bases like HO⁻ react at the partially positive hydrogens in H₃O⁺, not at the oxygen, despite its formal positive charge.

Key takeaways regarding formal charge and reactivity:

- Positive formal charges on oxygen and nitrogen do not indicate empty orbitals. Assume they have full octets.

- Positive formal charges on carbon do indicate empty orbitals (carbocations).

Understanding this distinction is vital for correctly interpreting reaction mechanisms and predicting reactivity based on formal charge and electron distribution.

6. Formal Charges on Halogens: Special Cases

Halogens can exhibit positive formal charges in a couple of notable scenarios.

Halonium Ions (Cl⁺, Br⁺, I⁺):

Halonium ions, such as Cl⁺, Br⁺, and I⁺, are often depicted with a positive formal charge and six valence electrons (and thus an empty p-orbital). While fluorine (F⁺) is highly reactive and less common in this form, heavier halogens (Cl, Br, I) can exist as halonium ions.

The larger size and greater polarizability of Cl, Br, and I allow them to stabilize a positive charge over a larger volume. These halonium ions can act as electrophiles, accepting electron pairs from Lewis bases to achieve a full octet.

Halogens Bonded to Two Atoms:

Halogens can also have positive formal charges when bonded to two other atoms. In these cases, the halogen atom does have a full octet. It’s important to recognize this distinction. In these situations, halogens with a positive formal charge will not typically act as electrophiles themselves. Instead, reactivity often occurs at an atom adjacent to the positively charged halogen.

When encountering positively charged halogens, carefully consider the bonding environment to determine if it’s a halonium ion (empty orbital) or a halogen with a full octet bonded to multiple atoms. This distinction is crucial for predicting reactivity patterns.

7. Conclusion: Mastering Formal Charge

By now, you should have a solid understanding of how to calculate formal charge and its significance in chemistry. Consistent practice with diverse examples is the key to mastery.

Let’s recap the key points:

- Formal Charge Formula: FC = VE – NBE – B

- Implicit Details: Be mindful of implicit lone pairs and C-H bonds in skeletal structures when calculating formal charges.

- Octet Rule and Positive Charges: Positively charged carbon has an empty orbital. Positively charged nitrogen and oxygen typically have full octets.

- Formal Charge vs. Reactivity: Formal charge is a useful tool, but it’s crucial to consider electronegativity and dipoles to fully understand reactivity. Hydronium ion (H₃O⁺) is a prime example where formal charge on oxygen doesn’t directly indicate the reactive site.

With these principles and continued practice, you will be well-prepared to confidently tackle formal charge calculations throughout your chemistry studies. Remember, formal charge is a powerful tool for understanding and predicting molecular behavior – master it, and you’ll unlock deeper insights into the world of chemistry.

Notes

Related Articles

Note 1. While we use “valence electrons” in the formal charge formula, it’s conceptually more accurate to think of it as a proxy for “valence protons” or the “effective nuclear charge.” Positive charge originates from protons in the nucleus. The number of valence electrons roughly corresponds to the nuclear charge experienced by the valence shell electrons.

Note 2. Nitrenes are exceptions to the octet rule for nitrogen. Also, when drawing less favorable resonance structures, we might intentionally depict atoms with incomplete octets.

Note 3. The concept of “formal” charge is analogous to “formal wins” in baseball. A pitcher might be credited with a win even if their performance wasn’t stellar, due to the rules of the game. Similarly, formal charge is an assignment based on rules and doesn’t always reflect the actual charge distribution in a molecule. See post: Maybe They Should Call Them, “Formal Wins” ?

Note 4. This chart illustrates the relationship between formal charge, valence, and geometry for first-row elements.

Quiz Yourself!

Click to Flip

(Advanced) References and Further Reading

1. Valence, Oxidation Number, and Formal Charge: Three Related but Fundamentally Different Concepts Gerard Parkin Journal of Chemical Education 2006 83 (5), 791 DOI: 10.1021/ed083p791

2. Lewis structures, formal charge, and oxidation numbers: A more user-friendly approach John E. Packer and Sheila D. Woodgate Journal of Chemical Education 1991 68 (6), 456 DOI: 10.1021/ed068p456